JICD,Vol.2,No.1,e002,2021

ENG / CHN / JPN / ESP

Mitigating The Impact of COVID-19 on Dental Education and The Resumption of Patient Care: The UT Health San Antonio Experience

Corresponding Author:

Enas A. Bsoul, DDS, MSc, MS

Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229

Email: [email protected]

Author:

Peter M. Loomer, BSc, DDS, PhD, MRCD(C), FACD

Professor and Dean, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

Email: [email protected]

Abstract

Purpose/Objectives: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on faculty, staff and students at UT Health San Antonio (UTHSA), School of Dentistry (SoD), and their readiness to resume dental practice with safety measures in place.

Methods: An observational survey study approved by UTHSA Institutional Review Board was distributed to members of UTHSA, SoD using Qualtrics software. The survey was completed anonymously. Data were analyzed using R statistical computing software, Chi-Square test and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test.

Results: Overall, the majority of respondents were satisfied with the resources UTHSA provides to help support them during the pandemic (91%), were confident in safety precautions and personal protective equipment at the school (90%), felt prepared to resume dental practice (81%), and agreed there are challenges (87%) and long-term impacts (94%) on dentistry. The majority were concerned about impacts of COVID-19 on UTHSA (94%) and on their general health, safety, physical and psychological well-being (86%).

Conclusions: There is significant health, psychological and economic impact of COVID-19 on dental professionals; hence, the need to improve safety, infection control precautions, psychological support, communications and programming around the COVID-19 pandemic and future challenges. Further research should evaluate the impact of the pandemic on community dental clinics, including the long-term effects on the oral health of the population.

Implications: Health professions, dental in particular are at the highest risk of COVID-19 infection and play an important role in preventing the transmission of the virus.

Key words:COVID-19, pandemic, impact, dental education, dental practice.

1. Introduction

In early December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology emerged in Wuhan City, China. All cases were linked to Wuhan's Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.1

The causative agent for the disease was identified as a 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The disease was subsequently called COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) in February, 2020. The betacoronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19 affects the lower respiratory tract manifesting as pneumonia in humans.2

COVID-19 is considered a relative of other CoV epidemics such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). On January 30, 2020, the outbreak was declared by WHO a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. On February 26, 2020, the first case of coronavirus, not first contracted in China, was recorded in the United States. The WHO raised the CoV epidemic threat to the "very high" level on February 28, 2020 and declared it a pandemic later in March.3

COVID-19 has been reported to more likely affect older males with other comorbidities, including respiratory disease, obesity and diabetes. The incubation period can vary between 7 to 24 days, with clinical symptoms ranging from none to mild (fever, dry cough and sore throat) to very severe with fatal complications and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.4

COVID-19, similar to other CoV infections, was reported as zoonotic, believed to have originated in bats and pangolins and later transmitted to humans. SARS-CoV-2 was profusely present in nasopharyngeal and salivary secretions of affected patients, its spread was mainly respiratory droplet/contact in nature.5

An article published by The New York Times magazine ranked the health professions at the highest risk of COVID-19 infection, amongst which dental professionals occupied the top tier of the ranking.6,7

Main transmission routes of COVID-19 are direct contact and droplet transmission. Another possible route is saliva and aerosol (airborne) transmission. The nature of dental procedures poses potential risks of infection transmission to dental care personnel and patients as they generate significant amounts of droplets and aerosols.6,8-11

Dental professionals, are especially at high risk of COVID-19 infection due to the peculiarity of dental practice; face-to-face communication with patients and frequent exposure to saliva, blood, and other body fluids. The use of sharp and high-speed rotary and ultrasonic instruments magnifies infection risk in dental practices, particularly from asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients, thus mandating strict and effective infection control protocols.6,9,11-14

Dental professionals play important roles in preventing the transmission of the virus. It is essential that they implement necessary precautions and infection control measures to maintain a healthy and safe environment for patients and themselves during the pandemic.8,10

In many countries, when compared to blood-borne infections, infection control information, education and practice regarding droplet and airborne infections in most dental schools’ curriculum are limited.12 In a U.S. survey, most schools were found to not have an independent course to teach infection control and only used classroom lectures and clinic demonstrations.15 Dental schools’ policies and protocols should be periodically re-evaluated and reprioritized to include a detailed contingency plan in case of future pandemics.16

A study in North America found that practice of dentistry was significantly impacted by COVID-19 pandemic in private practice and academic settings. Many dental professionals have reported increased work-related stress and anxiety due to the high occupational risk of infection and significantly increased tasks.17 A survey study by Hung et al,18 carried out in a dental school in Utah, found significant impact of COVID-19 on dental education, with increased levels of stress reported among dental students.

Shacham et al19 reported elevated psychological distress level experienced by Israeli dental staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. In a survey study in Hong Kong, all healthcare students including dental students reported high stress levels despite being confident in infection control procedures.20 A study conducted in China revealed that the psychological impact and anxiety of COVID-19 were rated as moderate-to-severe by about one-half and one-third of the respondents, respectively.21 Duruk et al22 found that more than 90% of Turkish dentists were concerned about themselves and their families.

A survey study evaluated Italian dentists’ perception of risks associated with resuming dental practice. Though dentists were properly informed on transmission modes, they were apprehensive and not confident in being able to work safely during COVID-19 outbreak.23

General dental practitioners from 30 different countries across the world were evaluated in a survey study that found more than two-thirds had elevated anxiety and fear due to the pandemic and being at high risk of contracting COVID-19. The majority were aware of recent dental treatment protocol changes and modified services according to recommended CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) guidelines.24

A survey study by Nelson et al25 assessed US public concerns and individual actions in response to the pandemic. The majority of respondents reported making changes to their lifestyle in response to COVID-19 with two-thirds being very or extremely concerned.

The impact of COVID-19 on dental education was immediate after announcing the need for social distancing and minimizing teaching, educational and clinical activities requiring face-to-face communication. Shifting to alternative teaching methods, such as online lectures, webinars and computer-based exams, were instituted. Dental students have been shown to be stressed and negatively impacted by the fear of getting infected during COVID crisis; therefore, an increased need for psychological support and counselling services has been needed.6

COVID-19 has negatively impacted dental education, research and clinical practice with possible long-term effects, such as a reduction in the number of future applicants.6 COVID-19 has also greatly impacted the medical/dental sector economy by significantly limiting clinical and surgical activities, a drastic intervention to protect the health and safety of people and contain the spread of the virus.26

3. Results

3.1 Demographics

The entire pool of faculty, staff and students at UTHSA, SoD was asked to voluntarily participate in a survey about the impact of COVID-19 on dental education and practice on the second half of the Spring Semester, 2020. Respondents were asked questions about their experience with being in a school setting and the response of the university to their concerns. A subset of respondents, those who came back to the school in the latter part of the semester to resume dental practice as part of their usual job duties or academic requirements, were asked about challenges related to resuming dental practice under new rules designed to reduce exposure to coronavirus.

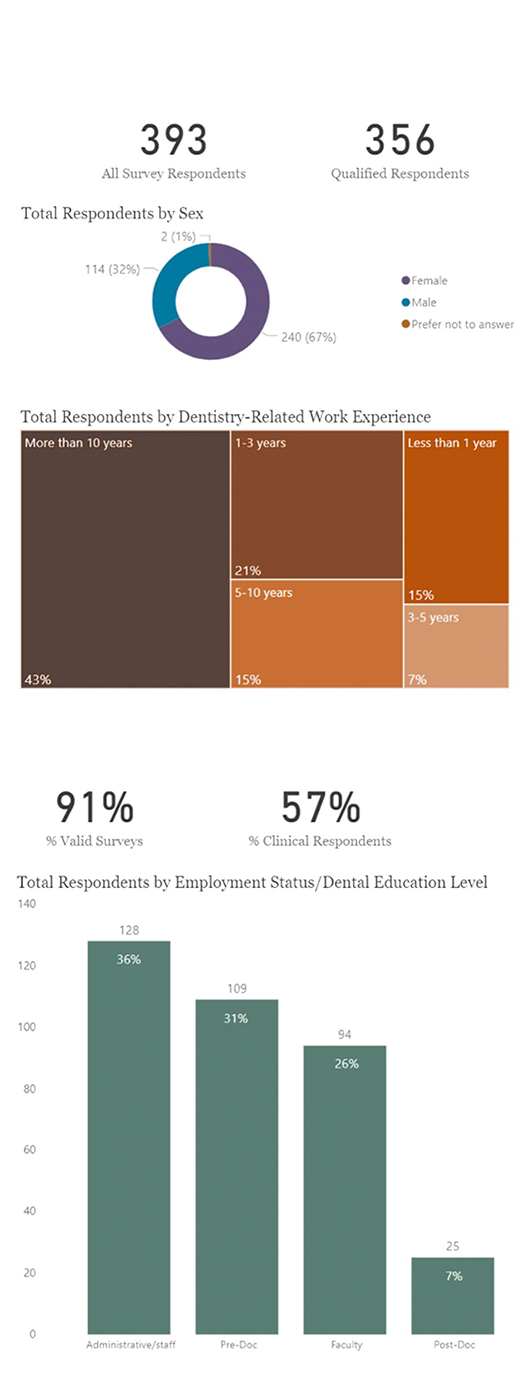

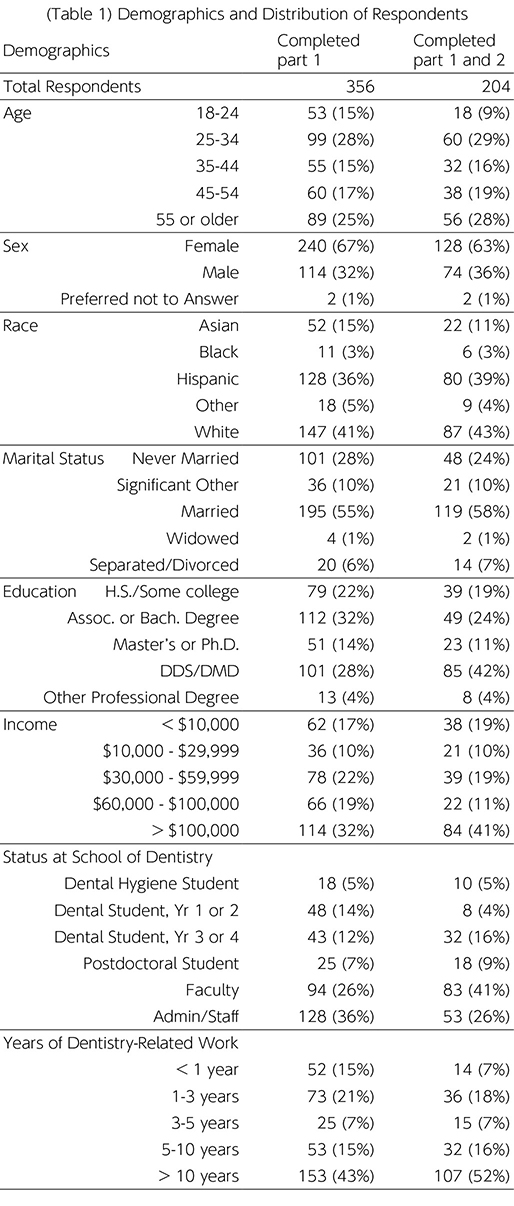

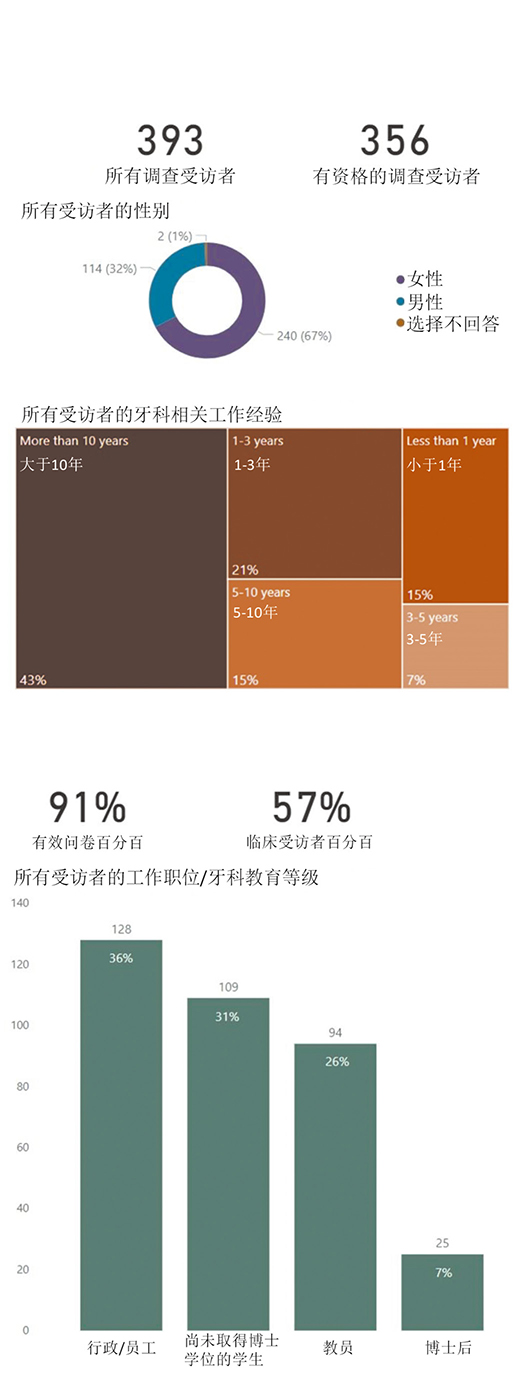

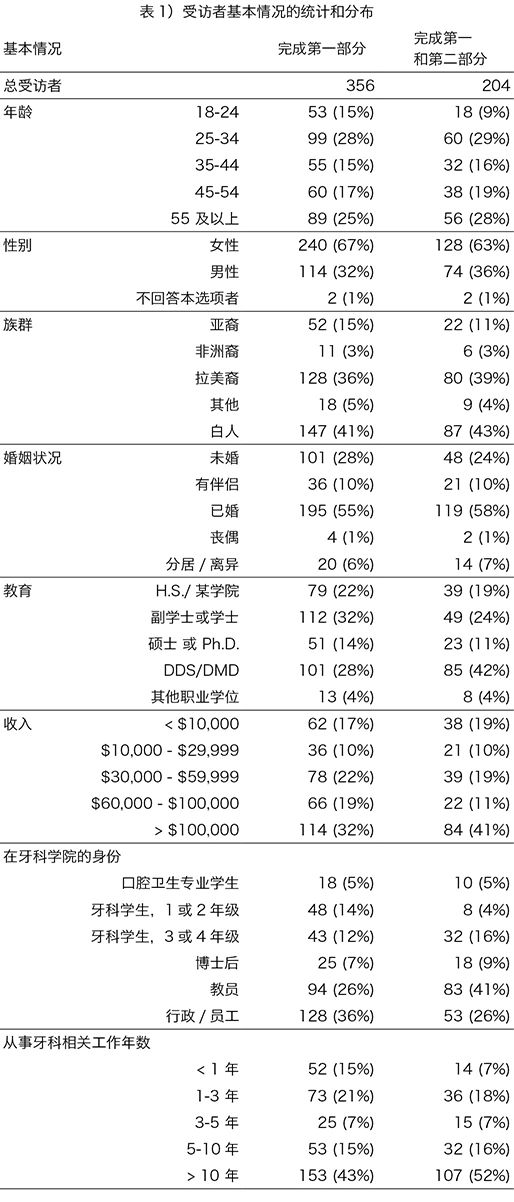

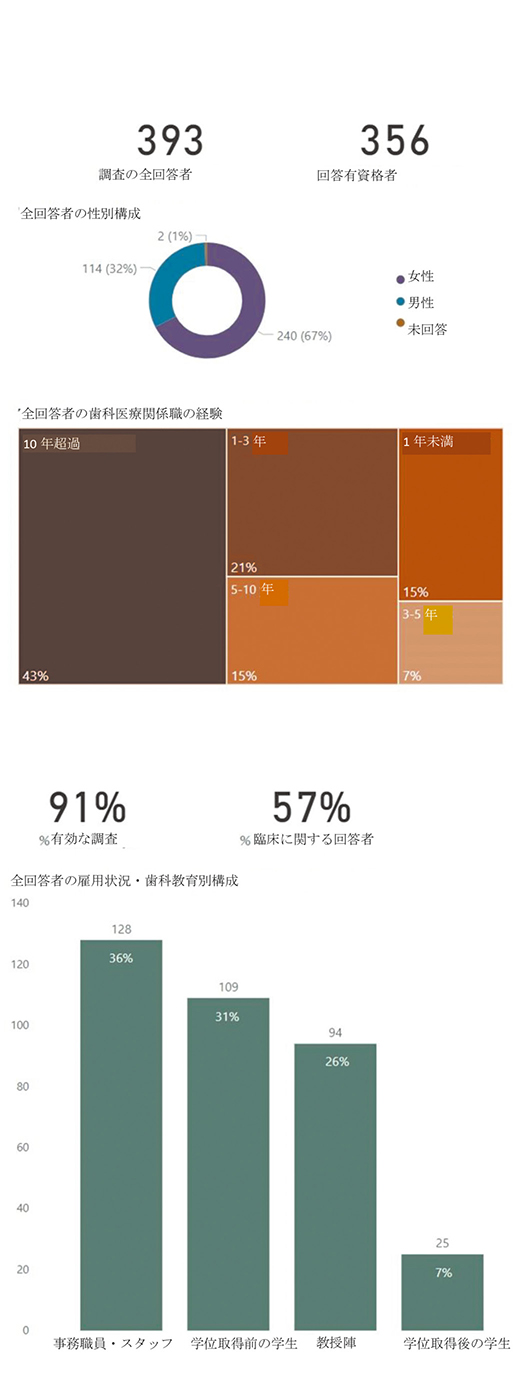

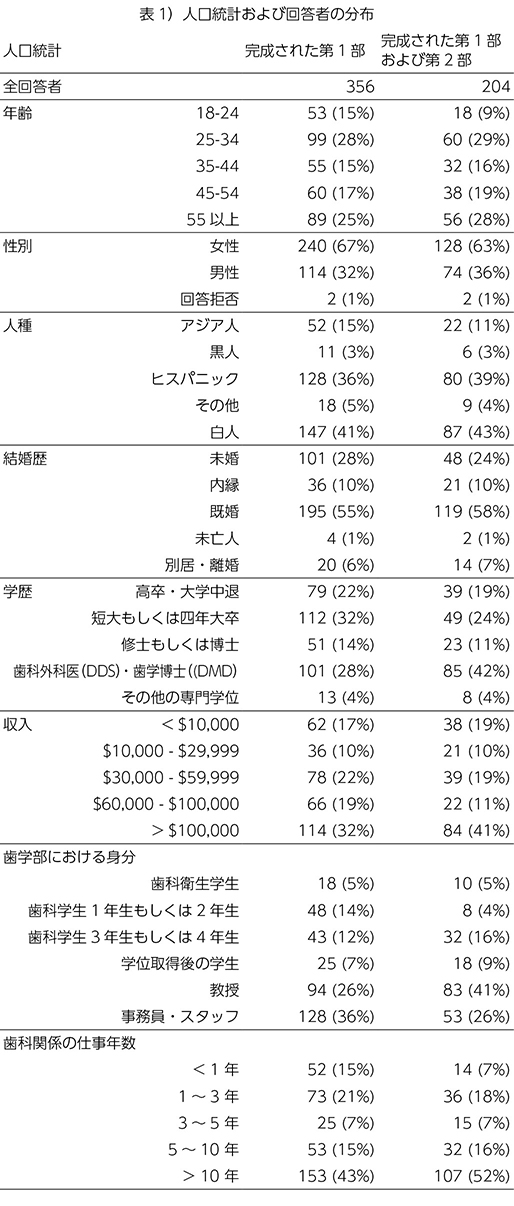

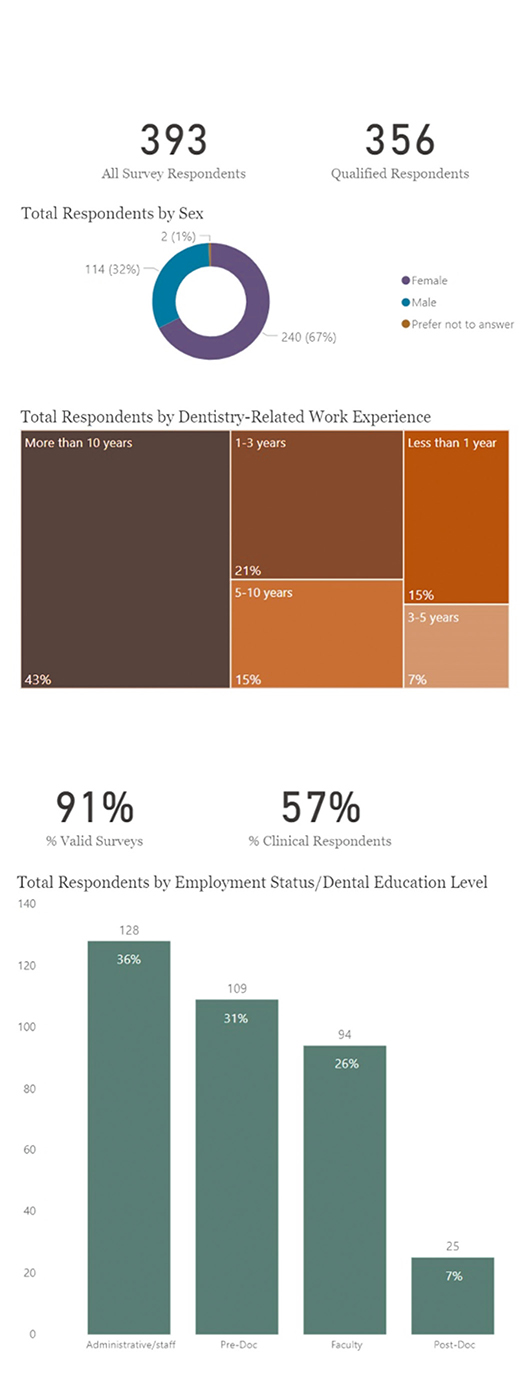

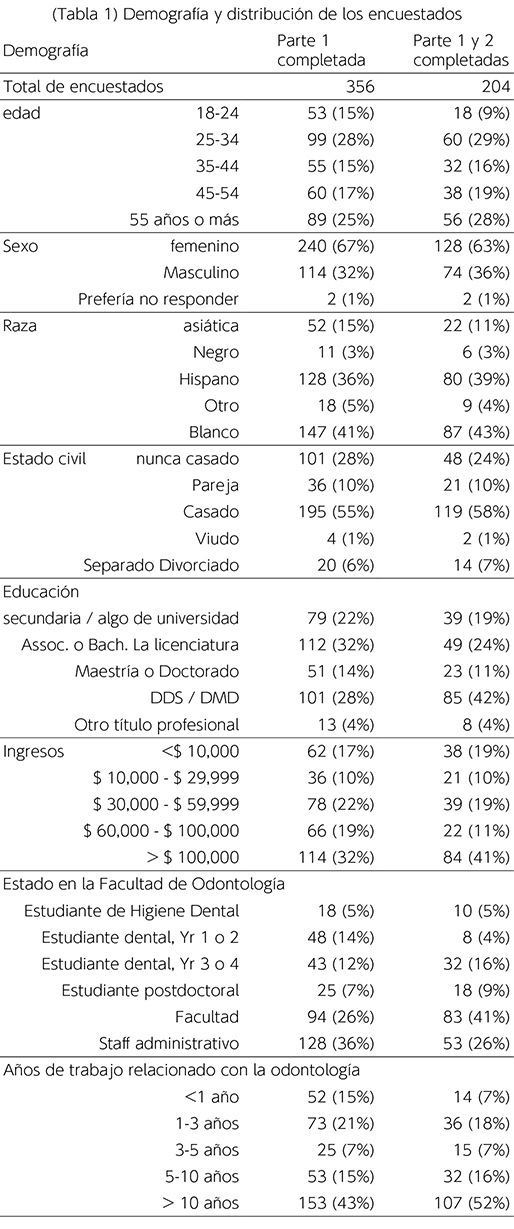

Out of 1230 invited respondents, a total of 356 respondents (29% response rate) associated with UTHSA, SoD completed the first part of the survey (general questions). Of that group, 204 (57%) completed the second part (clinically-related questions) of the survey. Demographics as reported by respondents are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Response rates among various types of total respondents were: 51% of faculty, 27% of administration/staff, 30% of predoctoral students (22% of dental students and 38% of dental hygiene students) and 24% of postdoctoral/advanced education students. Results were not weighted by response rate.

Respondents of the first part of the survey were generally representative of the total population at this UTHSA, SoD, which is located in a city with a high proportion of Hispanic residents but also attracts a large number of international students. Two-thirds of respondents in the first part were females. Respondents of the clinically-focused second part of the survey were slightly more likely to be male, older and Hispanic or White, were also more likely to be faculty and third- or fourth-year dental students.

3.2 General Challenges During the Pandemic

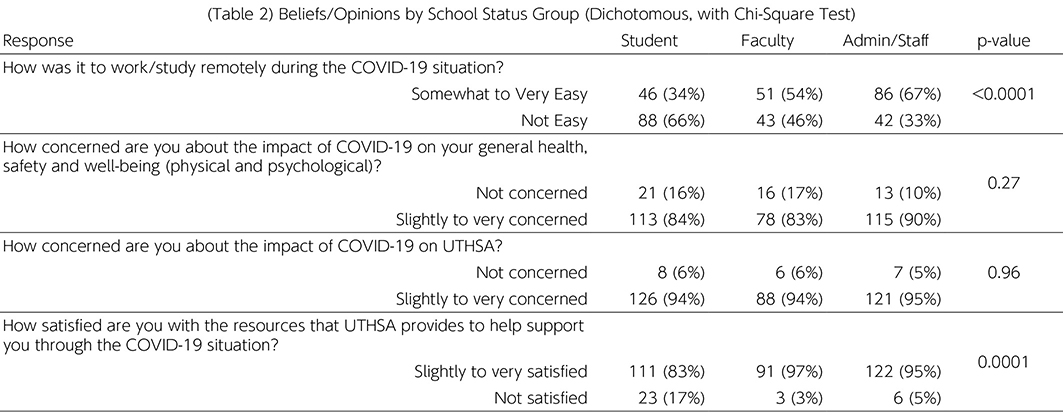

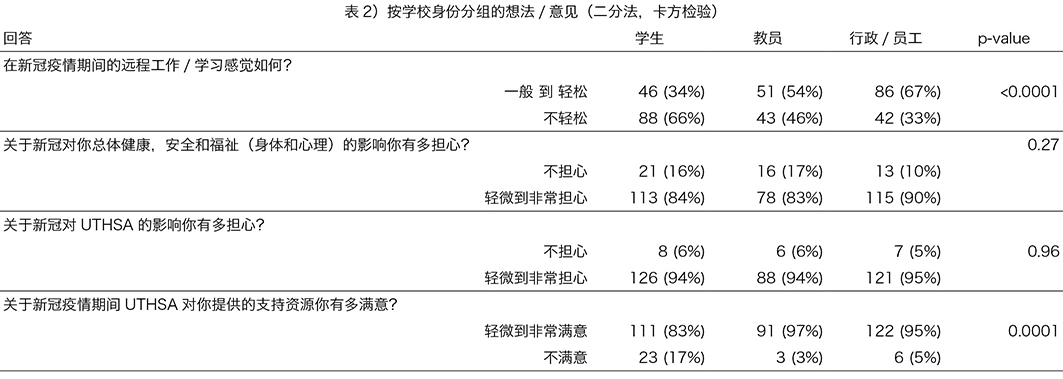

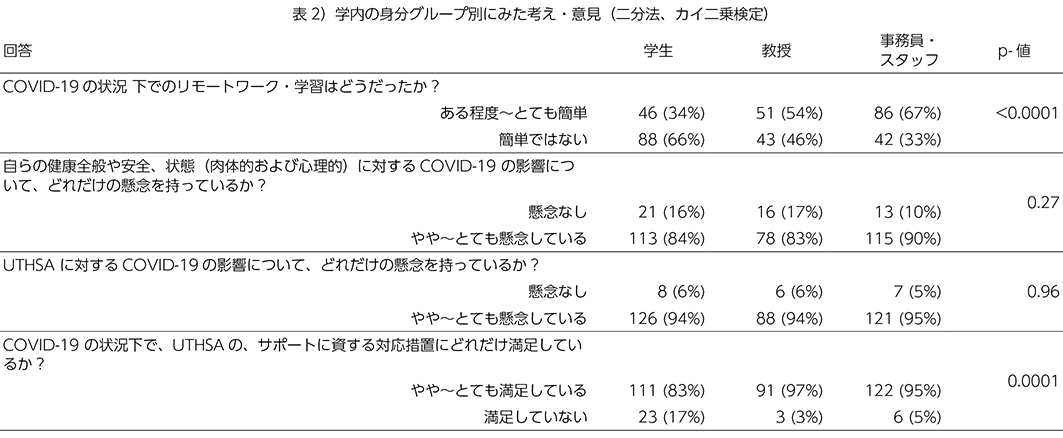

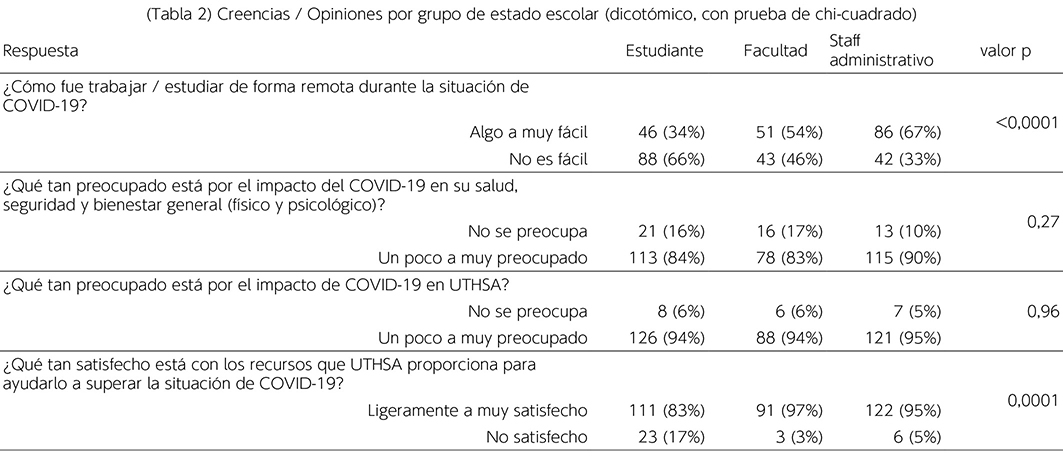

This series of questions asked respondents to provide their beliefs and opinions using a 5-point scale. Answers were compiled into two responses; A positive response (slightly/somewhat-very/agree) and a negative response (maybe-not/disagree), with Chi-Square statistical test used to determine if respondents’ groups were similar or if at least one was different from the others. The results of this portion of the survey, categorized according to job activity at school, are shown in Table 2.

The results revealed that 91% of respondents were satisfied with the resources UTHSA provided to help support them during the pandemic. More than half of faculty (54%) and administrative/staff (67%) groups found working/studying remotely during COVID-19 somewhat to very easy, while more than half of students (66%) found it not easy. Respondents were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their general health, safety and well-being (86%), as well as the impact on UTHSA (94%). Only 5 of total respondents reported themselves or a household member having testing positive for COVID-19 at the time of taking the survey.

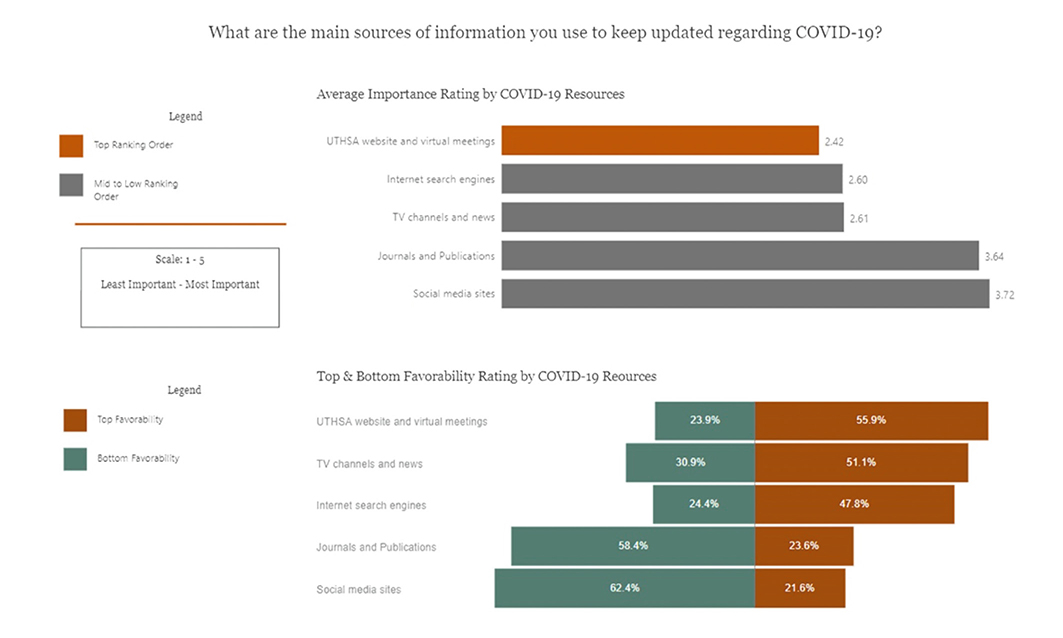

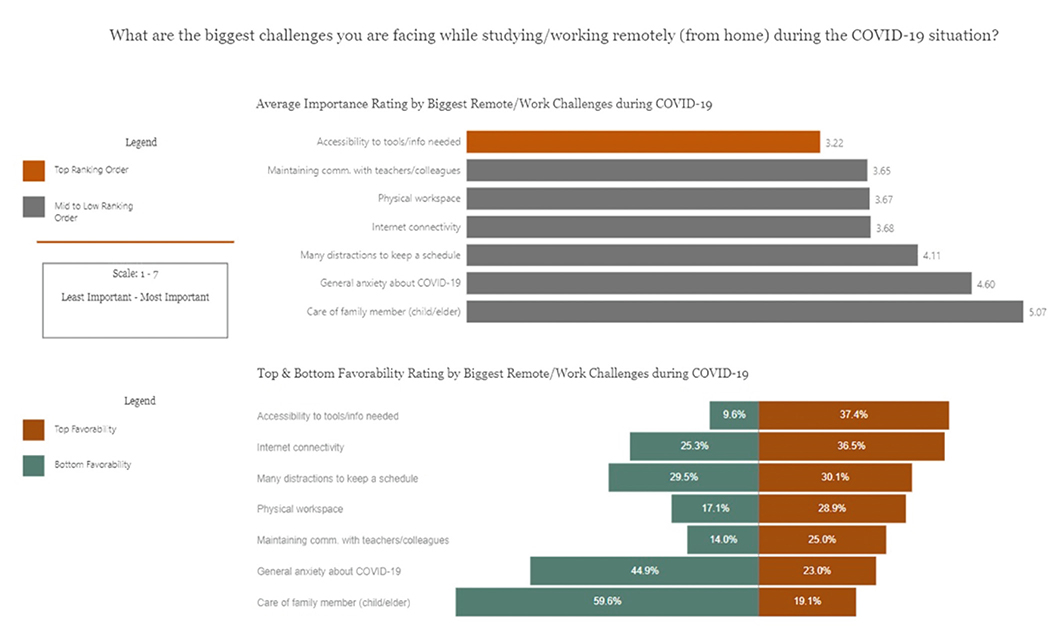

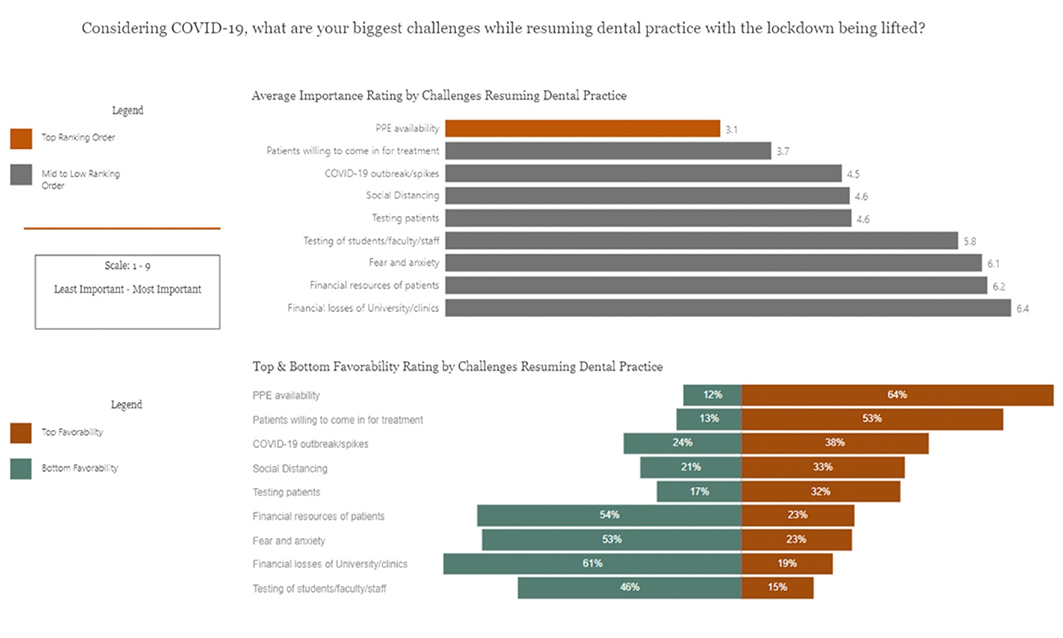

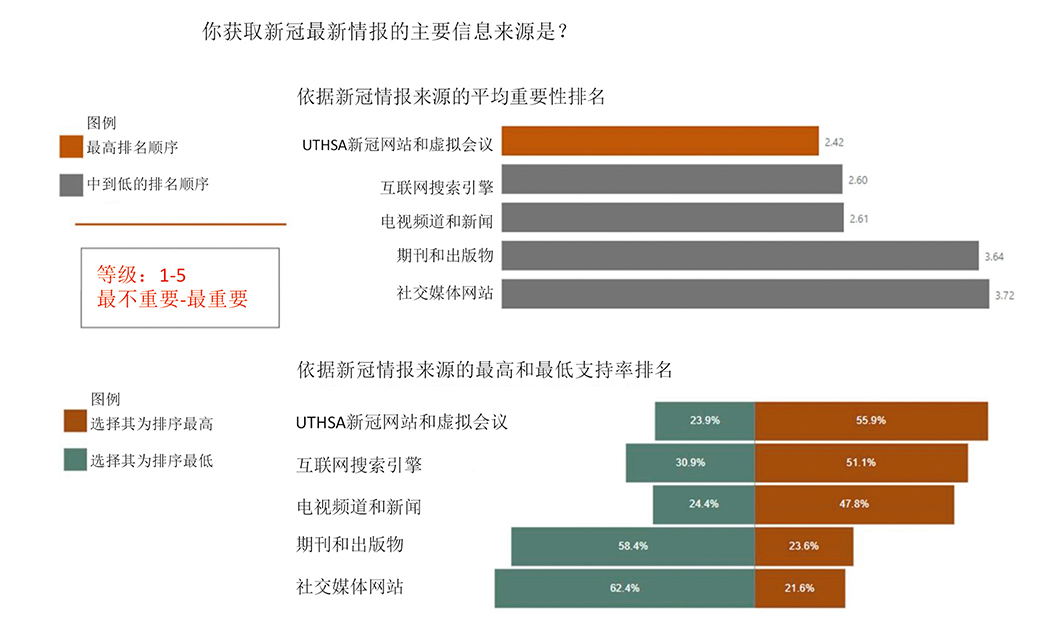

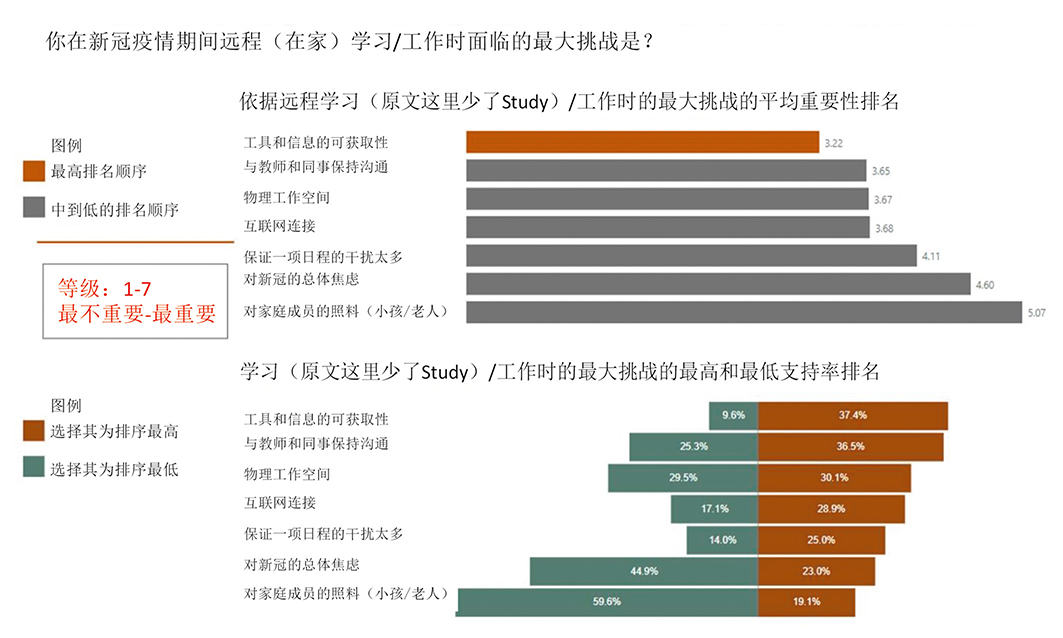

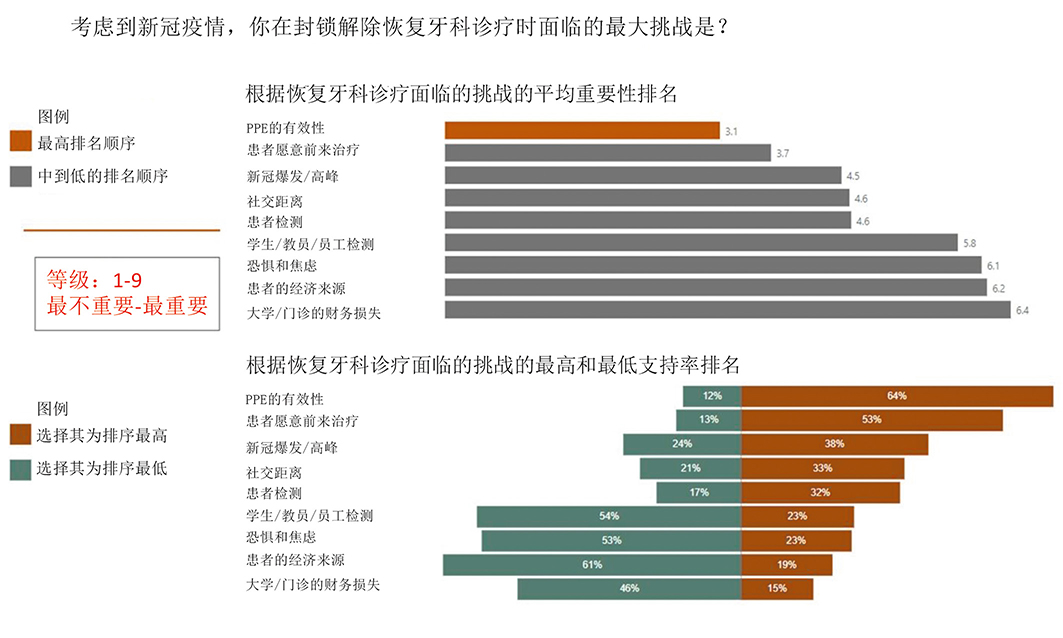

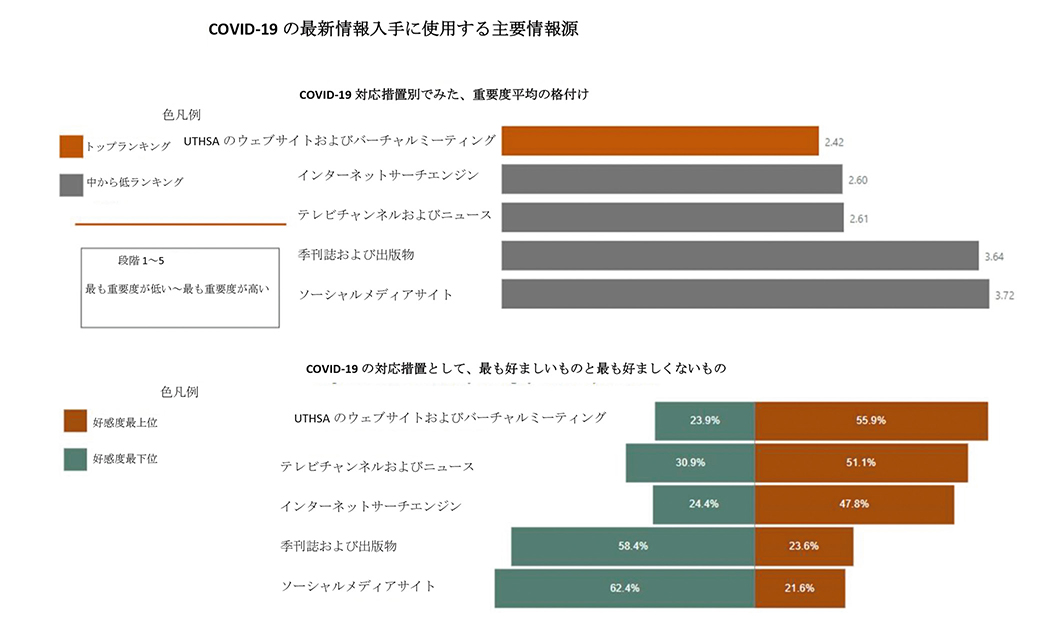

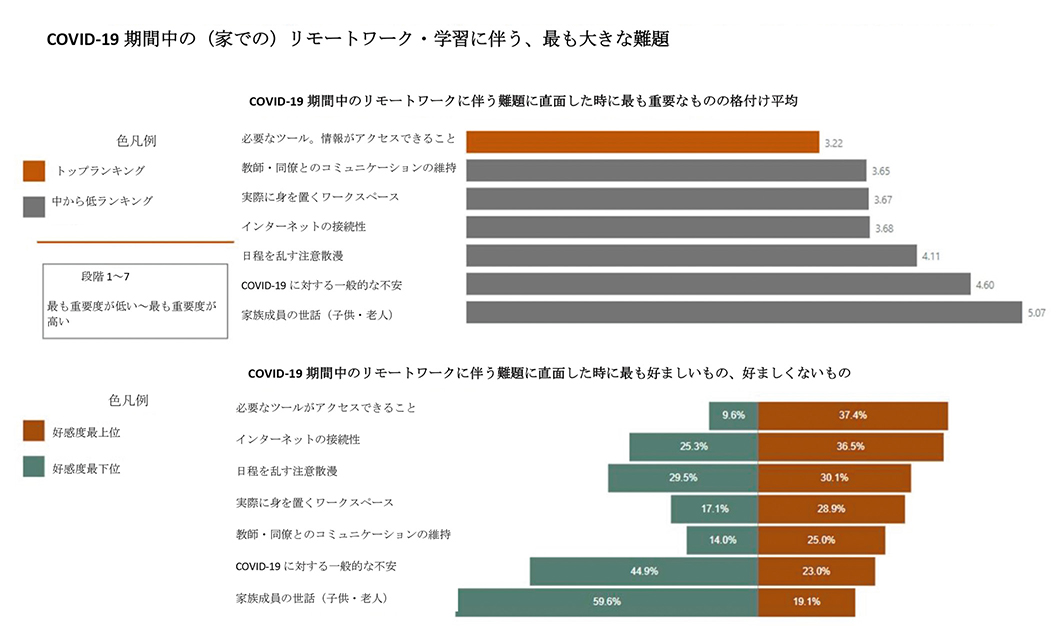

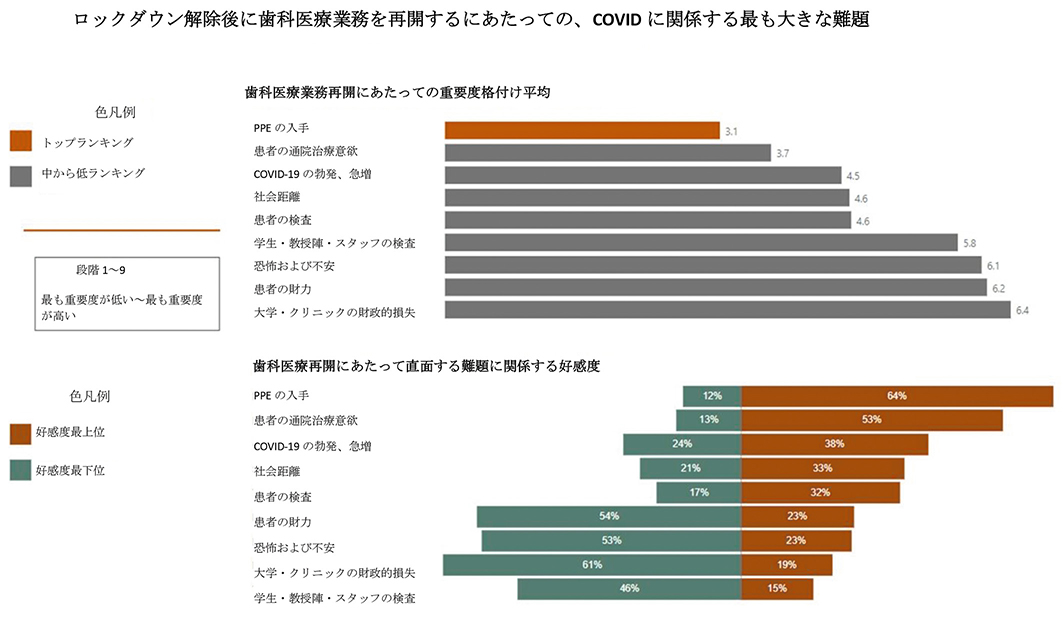

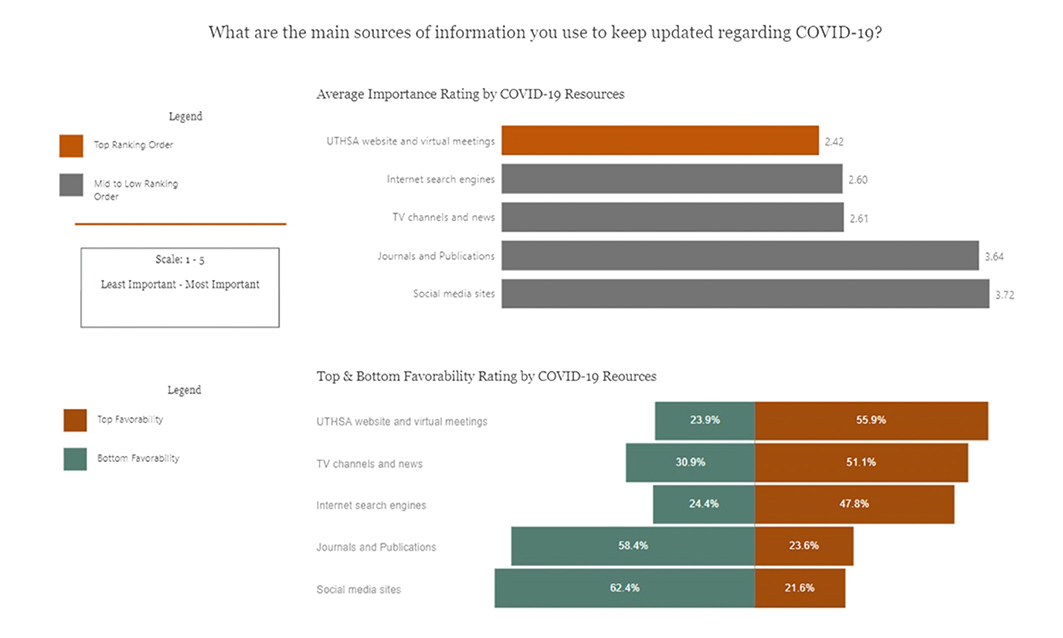

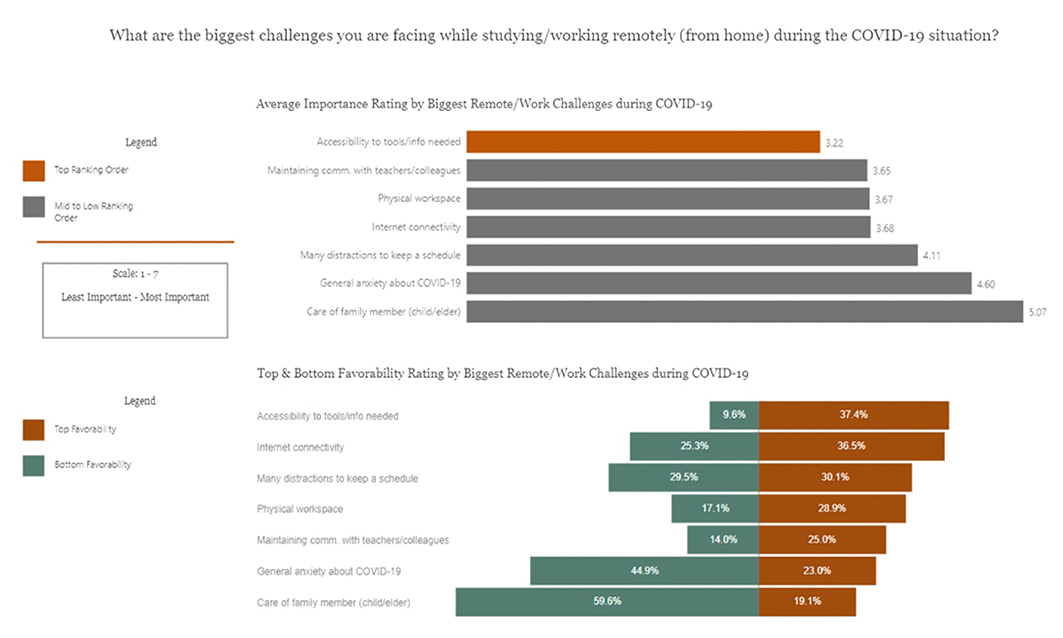

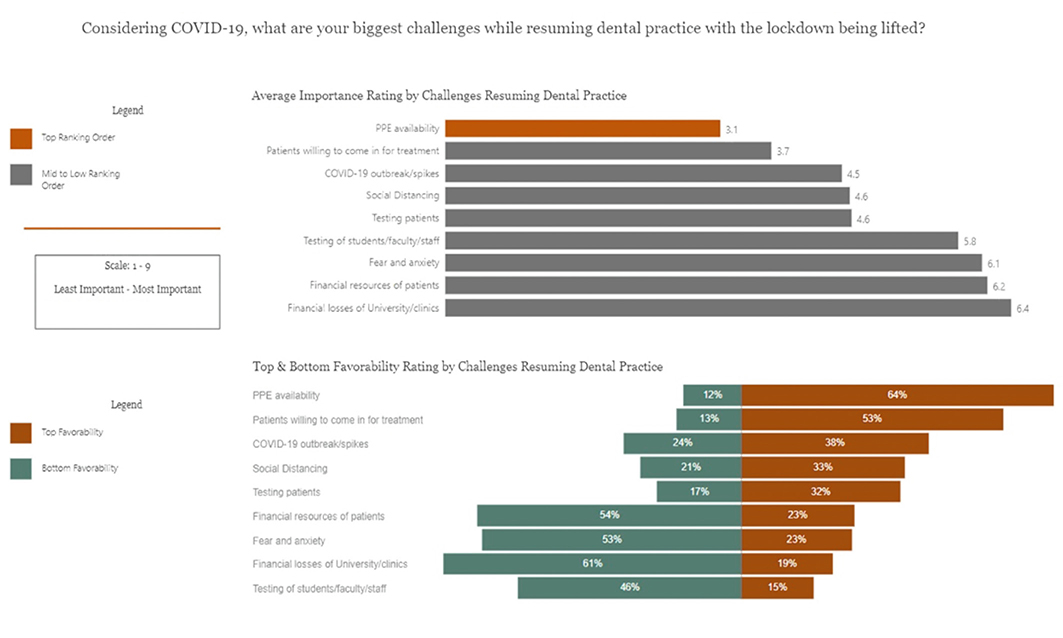

Another set of questions in the survey asked UTHSA, SoD respondents to rank order the importance of specific resources relative to two concepts: their main sources of information to keep updated regarding COVID-19 (Figure 2), and challenges associated with working/studying remotely (Figure 3). Two methods were selected to evaluate the responses: 1) Average Importance: where a value of 1 was assigned to the most important resource, 2 to the second most important and so on, after which a mean value of the importance score across all respondents was calculated, and 2) Favorability Rating: which reported the percentage of respondents that ranked the resource in either the top/bottom two or three, depending on the number of available responses to the question (Figures 2, 3, 4).

The SoD community study respondents rated the UTHSA COVID-19 website and virtual meetings in the top 2 of importance (56%) for a main source of information more often than any other resource, and had fewest number of members rate it at the bottom. Internet search engines and TV channels/news ranked nearly as important. Perhaps not surprisingly, journals and publications, which have a longer lead time to publish, were rated near the bottom by more than half the respondents. Interestingly, social media sites had the lowest favorability rating.

Regarding challenges, accessibility to tools and information was most often identified at the top while studying/working remotely. Internet connectivity, physical workspace, and maintaining communication with teaching staff and colleagues were also consistently reported near the top of importance. Anxiety about COVID-19 and taking care of a family member consistently rated among the least challenging for the community (45% and 60% respectively). Distractions that kept oneself from maintaining a regular schedule was a challenge of note; this was found among the most important challenges by about one-third of respondents, with more than half of students and younger age groups rating distractions near the top of importance.

3.3 Challenges Related to Resuming Dental Practice

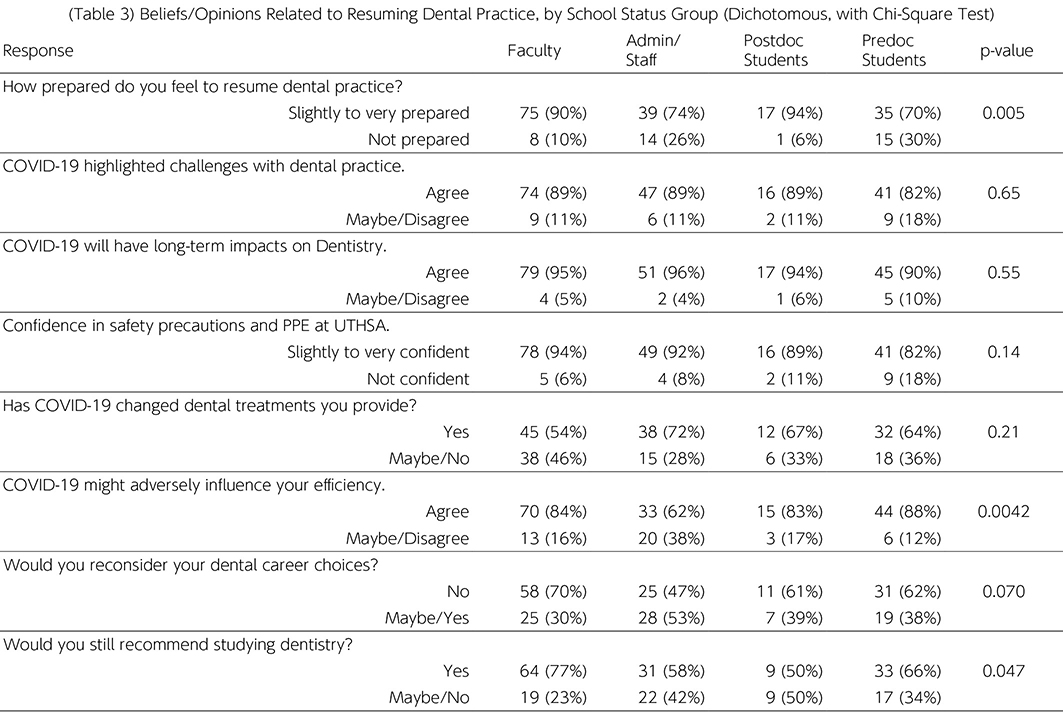

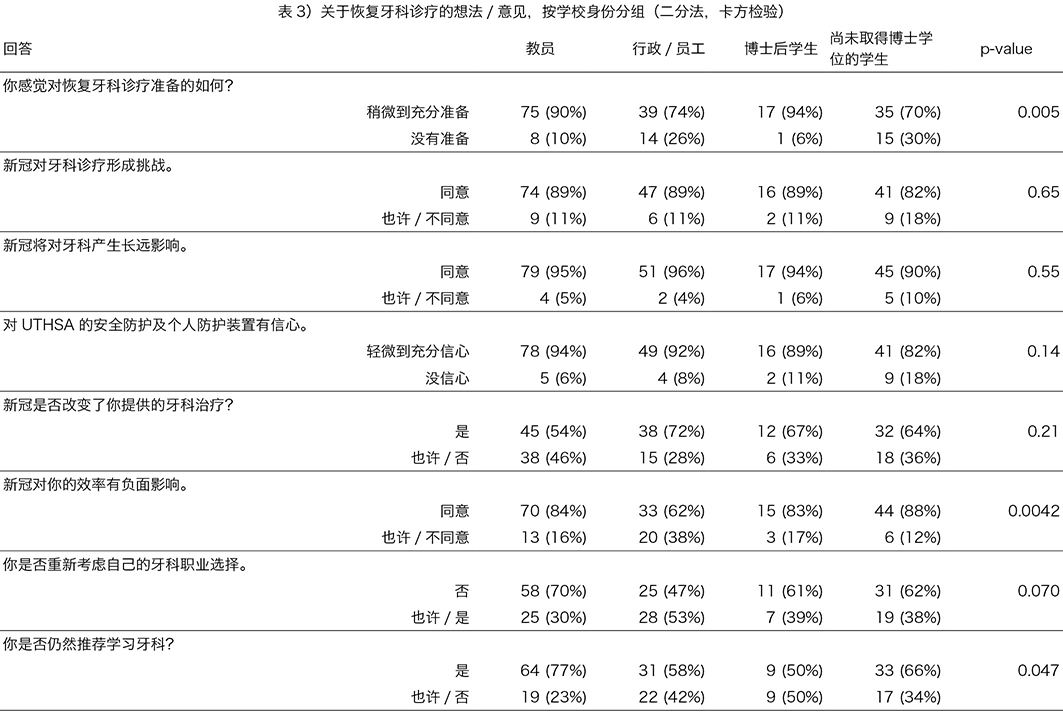

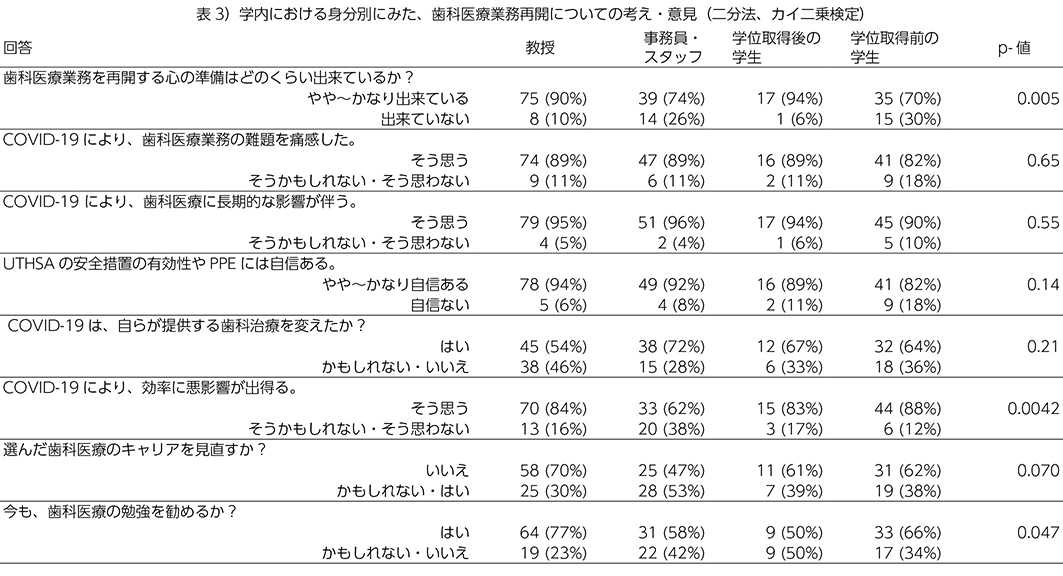

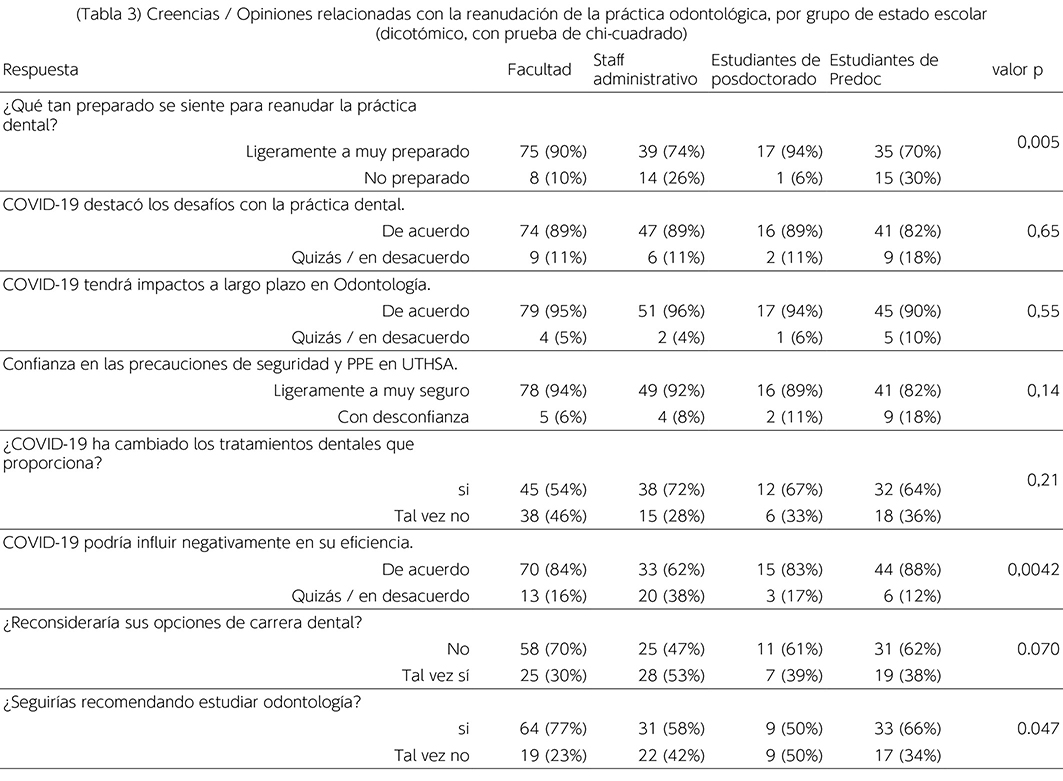

The 204 respondents in the clinical portion of the survey were asked to respond, using a 5-point scale, to 8 questions/statements regarding their beliefs and opinions. Responses are presented in Table 3, sub-categorized by status at SoD, and grouped into two categories. Statistical significance was awarded when p<0.05 using a Chi-square test to determine if at least one of the groups responded differently from the others.

3.3.1 Results of importance:

- More than 80% of all respondents felt at least slightly prepared to resume dental practice. Faculty and postdoctoral students, males, older and most experienced felt the most prepared.

- More than 87% agreed (somewhat or strongly) that there are challenges and long-term impacts on dentistry that need to be considered. Females were slightly more convinced of the challenges and impacts than males, and those with less dental experience were less convinced of long-term impacts than those with 5 or more years of experience.

- About 90% of respondents were slightly or more confident of the safety precautions and PPE provided by UTHSA for protecting them while performing aerosol-generating dental procedures. Faculty were most confident, while predoctoral students were most likely to have less confidence. Males and older group felt more confident.

- About 60% indicated that COVID-19 has caused them to change their patient’s dental treatments, and 80% felt COVID-19 would adversely influence their efficiency; the oldest group being most convinced in that regard. Females were more convinced about the need to change treatments while males were more concerned about efficiency. Dental hygiene students were most convinced about the need to change treatments and faculty were least convinced, whereas in terms of efficiency, the admin/staff were least concerned.

- About 60% would probably or definitely not reconsider their dental career choices and about 65% would probably or definitely recommend studying dentistry to others. Groups that were most ambivalent about their own career choices were administrative/staff, females and younger respondents.

Respondents were asked to rank order the importance of 9 challenges while resuming dental practice with the lockdown having been lifted (Figure 4). SoD community rated PPE availability and finding patients willing to come in for dental treatment in the top 3 of importance far more often (> 50%) than any other challenge. Although concerns regarding COVID-19 outbreak were rated near the top of challenges, fear and anxiety were rated as of least concern.

3.3.2 Results of importance:

- Postdoctoral students were far more concerned about PPE availability than any other group, and predoctoral students were the least concerned.

- Predoctoral students were the most concerned about patient availability, and were more concerned about patients’ financial resources to afford dental services. These concerns might reflect the students’ anxieties about obtaining adequate clinical experiences to satisfy graduation requirements.

- For faculty, testing for COVID-19 infection of patients was of higher concern, while fear and anxiety of least concern.

- Financial losses of the University and clinics were near the bottom of concern for all groups except for the faculty, oldest and most experienced groups.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a very serious public health challenge affecting the entire world, with significant impacts on healthcare workers, in particular those who provide dental care. Despite global efforts to control the disease, the incidence of COVID-19 continues to rise, with millions of infected patients and hundreds of thousands of deaths reported worldwide according to the most current data.

Due to the high risk of COVID-19 transmission in dental settings, a pause, early in the pandemic, on conventional educational activities created an opportunity to enhance alternative teaching methods and simulation clinical skills practice to partially alleviate the need for direct patient contact when appropriate.

According to Iyer et al,16 the biggest challenge for dental schools’ administration is balancing the important task of safeguarding the health of students, staff and patients, while keeping track of the changing environment, national policies, and ensuring continuity in students’ education. They emphasized on strengthening extramural activities and interprofessional education in the curricula to minimize disruptions to residents and students training, and to enable them be better prepared to help make an impact in the community during such a crisis and future pandemics.

Dental professionals are at high risk of COVID-19 infection due to unique nature of dental practice and face-to-face communication with patients.6,7,9,11-14 Yet, there has not been reported cases of transmission from clinician to patient, or vice versa. Infection control precautions and a healthy safe environment maintained to prevent COVID-19 transmission has been highly effective.8,10

In this study, respondents were concerned about impact of COVID-19 on their general health, safety and well-being as well as on UTHSA. Majority agreed there are challenges and long-term impacts on dentistry. In agreement, previous studies6,16-18 reported that COVID-19 has significantly and negatively impacted dental education and practice with potentially increased stress, anxiety and fear levels among dental staff and students, and with anticipated long-term effects on dental profession. Female gender, student status, and specific physical symptoms were associated with a greater psychological impact and higher levels of stress, anxiety and depression.21 Psychological impact from the COVID-19 pandemic was investigated in many countries (UK, US, Israel, Hong Kong, China, Turkey, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and others) and all reported high levels of stress, fear and anxiety.6,16-25

In agreement with our findings, Spagnuolo et al26 found that COVID-19 has profoundly impacted the economy of dental sector by significantly limiting clinical activities, a needed intervention to protect people and contain the spread of the virus.

The SoD community reported that the UTHSA COVID-19 website and twice-weekly virtual meetings with the SoD leadership as main source of information to keep updated during the pandemic, followed by internet search engines and TV channels and news. In contrast, Turkish dentists study reported that dentists mostly received COVID-19 information from official organizations websites and/or social media accounts, and only about one-quarter of respondents attended informational meetings on COVID-19.22

The majority of our respondents felt prepared to resume dental practice and were confident of the safety precautions and PPE at UTHSA would protect them while performing aerosols generating dental procedures. About 60% felt that COVID-19 has caused them to change dental treatments, and 80% felt it would adversely influence their efficiency. In comparison, De Stefani et al23 reported that Italian dentists considered COVID-19 infection highly dangerous, were not confident to resume dental practice safely, uncertain in regards to infection control measures and PPE, and were apprehensive about their health and economic/financial losses to their practices. Concerns regarding the use of and availability of appropriate PPE, as well as the awareness of recent treatment protocol changes during the pandemic, were also reported in several studies.6,22-24

This study has also evaluated other important issues such as challenges and difficulties while working/studying remotely and challenges while resuming dental practice. Various factors addressed were not previously evaluated in the literature, thus, shedding light on other COVID-19 related challenges impacting dental education and practice.

4.1 Limitations:

It is important to note that this study was conducted in the dental school early in the COVID-19 pandemic, and opinions may change as the pandemic progresses.

Future research should evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on community dental clinics, including the long-term effects on dentistry and oral health of the population.

5. Conclusions

This study found that respondents were satisfied with the resources UTHSA provided for support during the pandemic. They were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their general health, safety and well-being at UTHSA. The majority felt prepared to resume dental practice, were confident in the safety precautions in place and the availability of PPE at the school, and agreed that there are challenges and long-term impacts on dentistry.

The COVID-19 website at UTHSA and frequent virtual meetings were found to be the main sources of information to keep updated during the pandemic. While studying/working remotely, accessibility to tools and information was reported as a top challenge. PPE availability and patient flow were rated as top challenges while resuming dental practice. Although concerns regarding the COVID-19 outbreak were rated near the top of all challenges, fear and anxiety were rated near the bottom.

5.1 Implications for dental education and practice:

Health professions, dental in particular are at the highest risk of COVID-19 infection and play an important role in preventing the transmission of the virus.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude to the staff of the Office of the Dean of the School of Dentistry at UT Health San Antonio for their invaluable contribution to this study. Special thanks to Ms. Kristen Zapata for her kind support and help in distributing the survey. We would like to thank Mr. Michael Mader, Mr. Emmanuel Cortez and Mr. Jeremy Mercier for their valued assistance with the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang Y‐W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92: 401–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25678.

- Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International Journal of Surgery 76 (2020) 71–76.

- Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- N. Chen, M. Zhou, X. Dong, et al., Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study, Lancet (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

- Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM. Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19): Implications for Clinical Dental Care. J Endod. 2020;46(5):584-595. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008.

- Barabari P, Moharamzadeh K. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Dentistry-A Comprehensive Review of Literature. Dent J (Basel). 2020;8(2):53. Published 2020 May 21. doi:10.3390/dj8020053.

- The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk—The New York Times. [(accessed on 2 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker-risk.html.

- Ge, Z., Yang, L., Xia, J., Fu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science B, 21(5), 361–368. https://doi. org/10.1631/jzus.B2010010.

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9.

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9. Published 2020 Mar 3. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9.

- Ionescu AC, Cagetti MG, Ferracane JL, Garcia-Godoy F, Brambilla E. Topographic aspects of airborne contamination caused by the use of dental handpieces in the operative environment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(9):660-667. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.002.

- Ghai S. Are dental schools adequately preparing dental students to face outbreaks of infectious diseases such as COVID-19? J Dent Educ. 2020; 1-3. In Press.

- Pan Y, Liu H, Chu C, Li X, Liu S, Lu S. Transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2 and protective measures in dental clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Dent. 2020;33(3):129-134.

- Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):481-487. doi:10.1177/0022034520914246.

- Porteous NB, Bizra E, Cothron A, Yeh C-K. A survey of infection control teaching in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(2):187-194.

- Iyer P, Aziz K, Ojcius DM. Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:718–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12163.

- Wu KY, Wu DT, Nguyen TT, Tran SD. COVID-19’s impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral Dis. 2020;00:1–4. https:// doi.org/10.1111/odi.13444.

- Hung M, Licari FW, Hon ES, et al. In an era of uncertainty: Impact of COVID-19 on dental education. J Dent Educ. 2020;1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12404.

- Shacham M, Hamama-Raz Y, Kolerman R, Mijiritsky O, Ben-Ezra M, Mijiritsky E. COVID-19 Factors and Psychological Factors Associated with Elevated Psychological Distress among Dentists and Dental Hygienists in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2900. Published 2020 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082900.

- Wong JG, Cheung EP, Cheung V, Cheung C, Chan MT, Chua SE, McAlonan GM, Tsang KW, Ip MS. 2004. Psychological responses to the SARS outbreak in healthcare students in Hong Kong. Med Teach. 2004;26(7):657–659. doi:10.1080/01421590400006572.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. Published 2020 Mar 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729.

- Duruk G, Gümüşboğa ZŞ, Çolak C. Investigation of Turkish dentists' clinical attitudes and behaviors towards the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e054. doi:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0054.

- De Stefani A, Bruno G, Mutinelli S, Gracco A. COVID-19 Outbreak Perception in Italian Dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3867. Published 2020 May 29. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113867.

- Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, et al. Fear and Practice Modifications among Dentists to Combat Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. Published 2020 Apr 19. doi:10.3390/ijerph 17082821.

- Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, et al. US Public Concerns About the COVID-19 Pandemic from Results of a Survey Given via Social Media [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 7]. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1020-1022. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020. 1369.

- Spagnuolo G, De Vito D, Rengo S, Tatullo M. COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview on Dentistry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2094. Published 2020 Mar 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph 17062094.

Impact of COVID-19 on Dental Education and Practice

Start of Block: Demographics

Q1 What is your age?

- Under 18

- 18 - 24 years old

- 25 - 34 years old

- 35 - 44 years old

- 45 - 54 years old

- Over 55

Q2 What is your sex?

- Male

- Female

- Other

- Prefer not to answer

Q3 What is your race/ethnicity?

- White or Caucasian

- Hispanic or Latino

- Black or African American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other

Q4 What is your marital status?

- Never married

- Married

- Significant other

- Separated/Divorced

- Widowed

Q5 What is your annual household income?

- Less than $10,000

- $10,000 - $29,999

- $30,000 - $59,999

- $60,000 - $100,000

- More than $100,000

Q6 What is your educational level?

- Less than high school

- High school graduate

- Some college

- Bachelor's or Associate degree

- Master's degree

- Professional degree DDS/DMD

- Professional degree DH

- Professional degree/other

- PhD

Q7 What is your current employment status or dental education level at UT Health San Antonio Dentistry?

- Faculty

- Administrative/staff

- Dental student DS1

- Dental student DS2

- Dental student DS3

- Dental student DS4

- Dental hygiene student DH1

- Dental hygiene student DH2

- Graduate student (MS/MSc, PhD)

- Advanced education student/resident

- Post-doctoral fellow

End of Block: Demographics

Start of Block: General Questions

Q8 What are the main sources of information you use to keep updated regarding COVID-19? (Please arrange in order of importance with 1 being most important and 5 least important)

- UT Health San Antonio COVID-19 website and virtual meetings

- Internet search engines

- Social media sites

- TV channels and news

- Journals and Publications

Q9 How satisfied are you with the resources that UT Health San Antonio is providing to help support you through the COVID-19 situation?

- Very satisfied

- Moderately satisfied

- Slightly satisfied

- Not so satisfied

- Not satisfied at all

Q10 How easy or difficult is it for you to work/study remotely during COVID-19 situation?

- Very easy

- Somewhat easy

- Neither easy nor difficult

- Somewhat difficult

- Very difficult

Q11 What are the biggest challenges you are facing while studying/working remotely (from home) during COVID-19 situation? (Please arrange in order of importance with 1 being most important and 7 least important)

- Internet connectivity

- Physical workspace

- Accessibility to tools and information needed for my work/study

- Maintaining communication with teaching staff and colleagues/coworkers

- Many distractions to keep a regular schedule

- Family member/child care/eldercare

- General anxiety about COVID-19

Q12 How concerned are you about the impact of COVID-19 on UT Health San Antonio?

- Very concerned

- Moderately concerned

- Slightly concerned

- Not so concerned

- Not concerned at all

Q13 How concerned are you about the impact of COVID-19 on your general health, safety and well-being (physical and psychological)?

- Very concerned

- Moderately concerned

- Slightly concerned

- Not so concerned

- Not concerned at all

Q14 Have you or any of your household members tested positive for COVID-19?

Q15 How many years of dentistry-related work or academic teaching experience do you have?

- Less than 1 year

- 1-3 years

- 3-5 years

- 5-10 years

- More than 10 years

End of Block: General Questions

Start of Block: Clinical Questions

Q16 Are you involved in clinical dental practice/direct patient care/clinical teaching at UT Health San Antonio Dentistry?

Skip To: End of Block If v = No

Q17 Considering COVID-19, what are your biggest challenges while resuming dental practice with the lockdown being lifted? (Please arrange in order of importance with 1 being most important and 9 least important)

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) availability

- Patients willing to come in for treatment

- Keeping social distancing

- COVID-19 outbreak/spikes

- Fear and anxiety

- Testing of patients

- Testing of students, faculty and staff

- Financial losses of the University/clinics

- Financial resources of patients

Q18 How prepared do you feel you are to resume dental practice with the COVID-19 lockdown being lifted?

- Very prepared

- Moderately prepared

- Slightly prepared

- Not so prepared

- Not prepared at all

Q19 COVID-19 highlighted some challenges with the dental practice that should be taken into consideration to be better prepared in the future.

- Strongly agree

- Somewhat agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Somewhat disagree

- Strongly disagree

Q20 COVID-19 will have long-term impacts on the practice of Dentistry.

- Strongly agree

- Somewhat agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Somewhat disagree

- Strongly disagree

Q21 How confident do you feel that safety precautions and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE-including N95 respirators, face shields, minimizing aerosols) at UT Health san Antonio can protect you while performing dental procedures involving aerosols?

- Very confident

- Moderately confident

- Slightly confident

- Not so confident

- Not confident at all

Q22 Has COVID-19 caused you to change the types of dental treatment you provide patients?

- Definitely yes

- Probably yes

- Might or might not

- Probably not

- Definitely not

Q23 COVID-19 might adversely influence your efficiency in performing dental procedures.

- Strongly agree

- Somewhat agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Somewhat disagree

- Strongly disagree

Q24 In light of COVID-19, would you reconsider your dental career choices (clinical/academic/research/advanced education, etc)?

- Definitely yes

- Probably yes

- Might or might not

- Probably not

- Definitely not

Q25 In light of COVID-19, would you recommend studying dentistry to others?

- Definitely yes

- Probably yes

- Might or might not

- Probably not

- Definitely not

End of Block: Clinical Questions

Start of Block: Last Question

Q26 If you have any other comments regarding your experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, please write them below?

End of Block: Last Question

JICD,Vol.2,No.1,e002,2021

ENG / CHN / JPN / ESP

如何减轻新冠疫情对牙科教育及患者恢复诊疗的影响:

德克萨斯州大学圣安东尼奥牙科医学院的经验

Mitigating The Impact of COVID-19 on Dental Education and The Resumption of Patient Care: The UT Health San Antonio Experience

Corresponding Author:

Enas A. Bsoul, DDS, MSc, MS

Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229

Email: [email protected]

Author:

Peter M. Loomer, BSc, DDS, PhD, MRCD(C), FACD

Professor and Dean, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

Email: [email protected]

翻译:吴松涛, DDS, PhD

摘要(Abstract)

目的:本研究旨在评估新冠疫情对德克萨斯州大学圣安东尼奥(UTHSA)牙科学院(SoD)的教职员工和学生们的影响,以及他们在院内以安全方式恢复牙科诊疗的准备情况.

方法:经UTHSA大学机构评审委员会的批准,一项观察性调查研究问卷被通过Qualtrics软件发放到UTHSA和SoD成员手上.问卷被匿名完成.数据由R统计电脑软件分析,使用卡方检验和Wilcoxon-Mann-Whiney检验.

结果:总体上,大多数回答者对UTHSA在疫情期间提供给他们的支持资源感到满意(91%),对学校的安全措施及个人防护装备充满信心(90%),已经做好恢复牙科诊疗的准备(81%),认同疫情对牙科工作造成挑战(87%)和长期影响(94%).大多数人担心新冠疫情对 UTHSA(94%)的影响,也担心疫情对他们在总体健康,安全,身心福祉上的影响(86%).

结论:新冠疫情对牙科行业在健康,心理和经济层面有显著影响;因此,有必要针对新冠疫情和未来挑战,在安全,感染防控,心理支持,沟通和课程编排等方面做出改进.关于疫情对牙科诊所社群的影响,包括对人群口腔健康的长期影响还有待进一步的研究.

启示:医疗行业,特别是牙科是新冠感染的高风险行业,在防止病毒传播方面发挥着重要作用.

关键词(Key word):新冠病毒,疫情,影响,牙科教育,牙科诊疗.

Key words:COVID-19, pandemic, impact, dental education, dental practice.

1.引言

2019年12月初,中国武汉市爆发了不明病因的肺炎.所有病例都与武汉华南海鲜批发市场有关.1

该病的病原体被确定为2019新型冠状病毒(2019-nCoV).这种疾病后来在2020年2月被世界卫生组织(WHO)称为COVID-19(新型冠状病毒肺炎,简称新冠).导致新冠肺炎的β-冠状病毒(SARS-CoV-2)影响下呼吸道,在人类机体表现为肺炎.2

新冠病毒被认为与重症急性呼吸综合征冠状病毒(SARS-CoV)和中东呼吸综合征冠状病毒(MERS-CoV)等其他冠状病毒同属一族.2020年1月30日,世卫组织宣布疫情为国际公共卫生紧急事件.2020年2月26日,美国记录了第一例不是在中国境内首次感染的新冠病例.世卫组织于2020年2月28日将冠状病毒疫情威胁等级提高到“非常高”,稍后在3月宣布其为大流行.3

据报道,新冠病毒更可能影响有其他基础疾病(包括呼吸系统疾病,肥胖症和糖尿病)的老年男性.潜伏期可在7至24天之间不等,临床症状从无到轻微(发烧,干咳和喉咙痛),再到非常严重的致命并发症和急性呼吸窘迫综合征.4

报道称新冠与其他冠状病毒感染相似是人畜共患病,据信来源于蝙蝠和穿山甲,后来传播给人类.SARS-CoV-2在感染患者鼻咽和唾液分泌物中大量存在,其传播在本质上主要为呼吸道飞沫/接触性传播.5

《纽约时报》杂志曾发表的一篇文章,将医疗行业列为新冠感染风险最高的行业,而其中牙科专业更位居榜首.6,7

新冠的主要传播途径是直接接触和飞沫传播.另一种可能的途径是唾液和气溶胶(空气)传播.牙科操作的性质给牙科医护人员和患者带来了潜在的感染传播风险,因其会产生大量的飞沫和气溶胶.6,8-11

由于牙科诊疗的特殊性——与患者面对面的交流以及频繁接触唾液,血液和其他体液,让牙科从业者更容易感染新冠.在牙科操作中,使用锋利,高速旋转和超声波设备都会增加感染风险,特别是当治疗无症状或轻度症状的患者时,因此需要制定严格有效的感染控制方案.6,9,11-14

牙科从业人员在预防病毒传播方面发挥着重要作用.他们亟需采取必要的预防措施和感染控制措施,以便在疫情期间为病人和自己维持一个健康和安全的环境.

在许多国家,与血源性感染相比,大多数牙科学院课程中关于飞沫和空气传播感染的防控信息,教育和实践都存在不足.12 在美国的一项调查中,大多数学院没有独立的课程来教授感染控制,教学只分散在课堂授课和临床演示中.15 牙科学院的政策和方案应定期重新评估并调整优先次序,以包括一个详细的应急计划,用来预防未来的大流行.16

在北美的一项研究发现,在私人诊所和学术机构中,新冠疫情对牙科诊疗有显著影响.许多牙科从业人士报告说他们与工作相关的压力和焦虑增加了,这是由于要面对职业上更高的感染风险和显著增加的工作量.17 Hung等人18在犹他州一所牙科学院进行的一项调查研究发现,新冠对牙科教学有显著影响,据报道称,牙科学生的压力水平上升.

Shacham等19报道称,在新冠爆发期间,以色列牙科从业者经历了较高的心理痛苦水平.在香港的一项调查研究中,包括牙科学生在内的所有医学生都报告了高压力水平,尽管他们对感染控制程序充满信心.20 在中国进行的一项研究表明,约有一半和三分之一的受访者分别将新冠造成的心理影响和焦虑被评为中度至重度.21 Duruk等22发现,超过90%的土耳其牙医担心自己和家人.

另有一项调查研究评估了意大利牙医对恢复牙科诊疗相关风险的看法.尽管牙科医生被正确告知了病毒的传播方式,但他们对在新冠爆发期间是否能够安全工作感到担忧和缺乏信心.

还有一项调查研究对来自世界30个不同国家的全科牙医进行了评估,结果发现,超过三分之二的人因疫情流行和感染新冠的高风险而加剧焦虑和恐惧.大多数人都知道最近牙科治疗方案的变化和服务方式的改进,这些变化都基于疾病控制和预防中心(CDC)所推荐的指导方针.24

Nelson等25的一项调查研究评估了美国公众对疫情的担忧和个人应对疫情的行动.大多数受访者反馈称,他们对新冠的应对改变了自己的生活方式,其中三分之二的人非常或极度担忧.

在宣布需要保持社交距离和将需要面对面交流的教学,教育和临床活动缩减到最少之后,新冠对牙科教育的影响立即显现.学校开始转向其他教学方法,如线上讲座,网络研讨会和计算机考试.牙科学生由于害怕在新冠危机期间被感染而受到压力和负面影响,因此他们需要更多的心理支持和咨询服务.6

新冠对牙科教育,研究和临床诊疗均产生了负面影响,而且其影响可能长期持续,例如未来牙科学院的申请者数量的减少.6 新冠还显著限制临床和外科操作,这对医疗/牙科领域的经济状况产生重大影响,但这种限制是保护人民健康和安全,遏制病毒传播所必须的严厉干预措施.

3.结果

3.1

在2020年春季学期的下半学期,全体UTHSA, SoD的教职员工和学生被要求自愿参与一项关于新冠对牙科教育和诊疗影响的调查.受访者被问及他们在学校环境中的经历以及大学对他们关心问题的回应.一部分被调查者,即那些在本学期后半段回到学校,恢复牙科诊疗作为其日常工作职责或学术要求的人,被问及在为了减少接触冠状病毒的新规则下恢复牙科诊疗的相关挑战.

在1230名受邀参与问卷的人中,共有356名UTHSA, SoD 的相关受访者(29%的回复率)完成了调查的第一部分(一般问题).其中204人(57%)完成了调查的第二部分(临床相关问题).受访者报告的基本情况统计数据如表1和图1所示.各类受访者的回复率分别为:教员51%,行政/职员27%,尚未取得博士学位的学生30%(牙科专业学生22%和牙科卫生专业学生38%),博士后/高等教育学生24%.结果不按回复率加权.

调查第一部分的受访者基本代表了UTHSA, SoD的全体成员,牙学院所在城市拉美裔居民比例较高,但也吸引了大量的国际学生.在第一部分中,三分之二回答问卷的人是女性.而以临床为重点的第二部分调查的受访者中,男性,老年人,拉美裔或白人的可能性略高,同时也更有可能是教师和三或四年级的牙科学生.

3.2 疫情期间的一般挑战

这一系列的问题要求被调查者使用5分制来提供他们的想法和意见.答案被分为两种:一个是肯定回答(稍微/某种程度上-非常/同意),一个是否定回答(也许-不/不同意),用卡方统计检验来确定受访者的群体是否相似,或者至少有一个群体与其他群体不同.这部分调查的结果按受访者在学校的工作活动分类,见表2.

调查结果显示,91%的受访者对UTHSA在疫情期间提供的支持资源表示满意.半数以上的教师(54%)和行政/员工(67%)认为在疫情期间远程工作/学习某种程度上或非常容易,而半数以上的学生(66%)认为不容易.受访者担心新冠对他们的总体健康,安全和福祉的影响(86%),同时也担心对UTHSA的影响(94%).只有5%的受访者在接受调查时表示自己或家庭成员的新冠病毒检测呈阳性.

调查中的另一组问题要求UTHSA,SoD受访者根据两个概念对特定选项的重要性进行排序:他们跟踪疫情最新进展的主要信息来源(图2)和关于远程工作/学习的挑战(图3).研究选择了两种方法来评估回答:1)平均重要性:将分值1记给最重要的选项,将分值2记给第二重要的选项,依此类推,然后计算所有受访者重要性记分的平均值,2)支持率:这可以根据对问题的可用回答数值,反映出将资源排在前/后两位或三位的受访者百分比(图2,3,4).

在SoD区域学习的受访者将UTHSA新冠网站和虚拟会议作为主要信息来源排名前2位(56%),比其他任何来源的重要性都高,并且将它们排在最后的人数最少.互联网搜索引擎和电视频道/新闻几乎同样重要.超过一半的受访者对需要更长时间才能出版的期刊和出版物的排名接近垫底,这或许并不意外.有趣的是,社交媒体网站的支持率最低.

关于在远程学习/工作时面临的挑战,工具和信息的可获取性通常被认定是排名最高的.互联网连接,物理工作空间以及与教师和同事保持沟通也一直被排列在重要等级的前列.对新冠的焦虑和照顾家庭成员基本被评为群体中最不具挑战性的两类(分别为45%和60%).让自己无法维持正常日程的注意力干扰是一个值得注意的挑战;约三分之一的受访者发现,这是最重要的挑战之一,超过一半的学生和较年轻的年龄组认为注意力干扰几乎是最重要的.

3.3与恢复牙科诊疗相关的挑战

在这项调查的临床部分,204名受访者被要求用5分制的量表回答8个关于他们想法和意见的问题/陈述.回答内容在表3中列出,按在SoD的状态进行了分类,并分为两组.使用卡方检验确定是否至少有一个组的反应与其他组不同,当p<0.05时,认为有统计学显著性.

3.3.1重要的结果:

- 超过80%的受访者认为至少稍有准备恢复牙科诊疗.教师和博士后学生,男性,年龄较大和经验最丰富的人群感到最有准备.

- 超过87%的人同意(某种程度上或强烈地)需要考虑疫情对牙科形成的挑战和长期影响.女性比男性更相信这些挑战和影响,牙科经验较少的人比有5年或5年以上经验的人更不相信长期影响.

- 约90%的受访者对UTHSA提供的安全预防措施和个人防护装备(PPE)有部分或较大的信心,相信这些可以在进行产生气溶胶的牙科操作中保护他们.教员最有信心,而还没有获得博士学位的学生最可能缺乏信心.男性和年龄较大的人群更有信心.

- 约60%的人表示,新冠导致他们改变了患者的牙科治疗,80%的人认为新冠会对他们的效率产生不利影响;年龄最大的组别对此坚信不疑.女性更相信需要改变治疗方法,而男性更关心效率.口腔卫生专业的学生最相信需要改变治疗方法,而教员对此最不认同,而在效率方面,行政/员工则最不担心.

- 约60%的人可能不会或肯定不会重新考虑他们的牙科职业选择,约65%的人可能会或肯定会向其他人推荐学习牙科.对自己的职业选择最矛盾的群体是行政/员工,女性和年轻人.

受访者被要求对在解除封锁的情况下恢复牙科诊疗的9项挑战的重要性进行排序(图4).SoD群体将PPE的有效性和找到愿意接受牙科治疗的患者排在最重要挑战的前三位,比任何其他挑战都要重要(>50%).尽管对新冠爆发的担忧被排名很高,但恐惧和焦虑排名靠后.

3.3.2重要的结果:

- 博士后学生比任何其他群体都更关心PPE的有效性,而尚未获得博士学位的学生最不关心PPE的有效性.

- 尚未获得博士学位的学生最关心是否有患者,他们更担心患者用以支付牙科服务的经济来源.这些担忧可能反映了学生们对获得足够的临床经验以满足毕业要求的焦虑.

- 对于教员来说,他们更担忧对患者的新冠病毒感染的检测,而对恐惧和焦虑则最不担心.

- 除了教员,年龄最大和经验最丰富的群体,大学和门诊的财务损失几乎是排在所有群体关注序列的最底部.

4.讨论

新冠疫情是一次非常严重的公共卫生挑战,影响到整个世界,对医护人员,特别是那些提供牙科诊疗的人员造成了重大影响.尽管全球都在努力控制这种疾病,但新冠的病例数仍在持续上升,根据最新数据,全世界已有数百万感染者,数十万人因此丧命.

由于新冠病毒在牙科环境中传播的高风险,在疫情早期暂停了传统的教育活动,这为促进替代教学方法和模拟临床技能实践创造了机会,这可以在一定情况下部分缓解直接接触患者的需要.

Iyer等16认为,牙科学院管理面临的最大挑战是在维护学生,教职员工和患者健康的重要任务,与追踪不断变化的环境,国家政策和确保学生教育的连续性之间保持平衡.他们强调在课程中加强校外活动和跨专业教育,以尽量减少对住院医师和学生培训的干扰,使他们能够更好地做好准备,来在这次危机和未来的各种疫情之中,对社群产生正面影响.

由于牙科诊疗的独特性以及与患者面对面的交流,牙科从业人员感染新冠的风险很高.6,7,9,11-14 然而,还没有从医生到患者,或患者到医生的传播病例报道.用感染控制的预防措施和保持健康安全的环境来防止新冠的传播已经非常有效.

在这项研究中,受访者关注新冠对他们的总体健康,安全和福祉以及对UTHSA的影响.大多数人都认为牙科学面临挑战和长期影响.与此一致,先前的研究6,16-18报道称,新冠对牙科教育和诊疗产生了显著的负面影响,可能增加牙科从业人员和学生的压力,焦虑和恐惧水平,预计会对牙科行业产生的长期影响.女性,学生和特定身体症状等因素往往会造成更大的心理影响和更高水平的压力,焦虑和抑郁.21 在许多国家和地区(英国,美国,以色列,香港,中国,土耳其,意大利,沙特阿拉伯,巴基斯坦等)对于新冠疫情造成的心理影响都进行了调查,所有调查都显示较高水平的压力,恐惧和焦虑.6,16-25

与我们的研究结果一致,Spagnuolo等26发现新冠对临床活动的明显限制,已经深刻地影响了牙科行业的经济状况,但这种限制是保护人类和遏制病毒传播的必要干预措施.

SoD人群反馈称,UTHSA新冠网站和每周两次的与SoD领导层的虚拟会议是他们跟踪疫情最新进展的主要信息来源,之后是互联网搜索引擎,电视频道和新闻.相比之下,土耳其牙医研究报告称,那里的牙医大多从官方机构网站和/或社交媒体账户接收新冠信息,只有约四分之一的受访者参加了关于新冠信息的会议.22

本次大多数受访者感觉已经准备好恢复牙科诊疗,并相信UTHSA的安全预防措施和个人防护用品将在产生气溶胶的牙科操作中保护他们.约60%的人认为新冠导致他们改变了牙科治疗方法,80%的人认为这会对他们的效率产生不利影响.相比之下,De Stefani等23报道说,意大利牙医认为新冠感染非常危险,对安全恢复牙科诊疗没有信心,对感染控制措施和PPE感到不确定,并且对他们的健康和诊疗相关的经济/财务损失感到忧虑.还有一些研究报道了对适当的个人防护装备的使用和有效性的关注,以及对疫情期间最新治疗方案变化的认识.6,22-24

本研究还评估了其他重要问题,如远程工作/学习时面临的挑战和困难,以及恢复牙科诊疗时面对的挑战.这里提到的多种因素在之前文献中未有评估,因此本文阐明了其他影响牙科教育和诊疗的新冠相关挑战.

4.1局限性:

值得注意的是,这项研究是在新冠疫情早期在牙科学校进行的,随着疫情的进展,人们的看法可能会改变.

关于疫情对牙科诊所社群的影响,包括对人群口腔健康的长期影响还有待进一步的研究评估.

5.结论

这项研究发现,受访者对UTHSA在疫情期间提供的支持资源感到满意.他们担心新冠对他们在UTHSA的总体健康,安全和福祉的影响.大多数人已经准备好恢复牙科诊疗,对学校的安全预防措施和个人防护用品的有效性充满信心,并认同疫情对牙科形成了挑战和长期影响.

研究发现,UTHSA的新冠网站和频繁的虚拟会议是疫情期间跟进疫情发展最新情况的主要信息来源.在远程学习/工作时,对工具和信息的可获取性被认为是最大的挑战.PPE的有效性性和患者量被评为恢复牙科诊疗的最大挑战.尽管对新冠爆发的担忧在所有挑战中位居前列,但恐惧和焦虑都排名靠后.

5.1对牙科教育和诊疗的启示:

医疗行业,尤其是牙科行业,是感染新冠风险最高的行业,在防止病毒传播方面发挥着重要作用.

致谢

作者谨向德克萨斯大学圣安东尼奥牙科医学院院长办公室的工作人员表示最深切的感谢,感谢他们对本研究的宝贵贡献.特别感谢Kristen Zapata女士在分发调查报告时给予的支持和帮助.还要感谢Michael Mader先生,Emmanuel Cortez先生和Jeremy Mercier先生在数据分析方面给予的宝贵协助.

利益冲突:作者声明没有利益冲突.

参考文献

- Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang Y‐W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92: 401–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25678.

- Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International Journal of Surgery 76 (2020) 71–76.

- Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- N. Chen, M. Zhou, X. Dong, et al., Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study, Lancet (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

- Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM. Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19): Implications for Clinical Dental Care. J Endod. 2020;46(5):584-595. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008.

- Barabari P, Moharamzadeh K. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Dentistry-A Comprehensive Review of Literature. Dent J (Basel). 2020;8(2):53. Published 2020 May 21. doi:10.3390/dj8020053.

- The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk—The New York Times. [(accessed on 2 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker-risk.html.

- Ge, Z., Yang, L., Xia, J., Fu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science B, 21(5), 361–368. https://doi. org/10.1631/jzus.B2010010.

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9.

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9. Published 2020 Mar 3. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9.

- Ionescu AC, Cagetti MG, Ferracane JL, Garcia-Godoy F, Brambilla E. Topographic aspects of airborne contamination caused by the use of dental handpieces in the operative environment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(9):660-667. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.002.

- Ghai S. Are dental schools adequately preparing dental students to face outbreaks of infectious diseases such as COVID-19? J Dent Educ. 2020; 1-3. In Press.

- Pan Y, Liu H, Chu C, Li X, Liu S, Lu S. Transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2 and protective measures in dental clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Dent. 2020;33(3):129-134.

- Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):481-487. doi:10.1177/0022034520914246.

- Porteous NB, Bizra E, Cothron A, Yeh C-K. A survey of infection control teaching in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(2):187-194.

- Iyer P, Aziz K, Ojcius DM. Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:718–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12163.

- Wu KY, Wu DT, Nguyen TT, Tran SD. COVID-19’s impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral Dis. 2020;00:1–4. https:// doi.org/10.1111/odi.13444.

- Hung M, Licari FW, Hon ES, et al. In an era of uncertainty: Impact of COVID-19 on dental education. J Dent Educ. 2020;1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12404.

- Shacham M, Hamama-Raz Y, Kolerman R, Mijiritsky O, Ben-Ezra M, Mijiritsky E. COVID-19 Factors and Psychological Factors Associated with Elevated Psychological Distress among Dentists and Dental Hygienists in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2900. Published 2020 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082900.

- Wong JG, Cheung EP, Cheung V, Cheung C, Chan MT, Chua SE, McAlonan GM, Tsang KW, Ip MS. 2004. Psychological responses to the SARS outbreak in healthcare students in Hong Kong. Med Teach. 2004;26(7):657–659. doi:10.1080/01421590400006572.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. Published 2020 Mar 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729.

- Duruk G, Gümüşboğa ZŞ, Çolak C. Investigation of Turkish dentists' clinical attitudes and behaviors towards the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e054. doi:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0054.

- De Stefani A, Bruno G, Mutinelli S, Gracco A. COVID-19 Outbreak Perception in Italian Dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3867. Published 2020 May 29. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113867.

- Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, et al. Fear and Practice Modifications among Dentists to Combat Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. Published 2020 Apr 19. doi:10.3390/ijerph 17082821.

- Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, et al. US Public Concerns About the COVID-19 Pandemic from Results of a Survey Given via Social Media [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 7]. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1020-1022. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020. 1369.

- Spagnuolo G, De Vito D, Rengo S, Tatullo M. COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview on Dentistry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2094. Published 2020 Mar 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph 17062094.

JICD,Vol.2,No.1,e002,2021

ENG / CHN / JPN / ESP

COVID-19 の歯科医療教育への影響を最小限に抑え,患者治療を再開する: UT Health San Antonio の経験

Mitigating The Impact of COVID-19 on Dental Education and The Resumption of Patient Care: The UT Health San Antonio Experience

Corresponding Author:

Enas A. Bsoul, DDS, MSc, MS

Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229

Email: [email protected]

Author:

Peter M. Loomer, BSc, DDS, PhD, MRCD(C), FACD

Professor and Dean, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

Email: [email protected]

Abstract

目的・目標:本研究の目的は,COVID-19のパンデミックがUT Health San Antonio(UTHSA)歯学部(School of Dentistry: SoD)の教授陣およびスタッフ,実習生に及ぼす影響,更に歯科医療実務再開に向けての安全対策の準備状況を評価するところにある.

手段:UTHSA学会審査委員会が承認した観察調査は,Qualtricsのソフトウェアを用いてUTHSA, SoDの成員に配布され,本調査は匿名で実施された.データ分析は,R 統計計算ソフトウェア,カイ二乗検定およびWilcoxon-Mann-Whitney検定を用いて行われた.

結果:全体的に,過半数の回答者は,パンデミック期間におけるUTHSAのサポート力や対応力に満足し(91%),構内における安全対策や個人防護具(PPE)の有効性に自信を持ち(90%),歯学医療業務を再開する心の準備が整い(81%),歯科医療に今後も難題が発生する(87%)更に長期的な影響が及ぶ(94%)との見方で一致した.過半数が,COVID-19のUTHSAに対する影響(94%)更に,自らの健康全般,安全性,身体的および精神的健康(86%)に懸念を示した.

結論:COVID-19は歯科医療従事者に,健康面や精神面,経済面において多大な影響を及ぼしている.従って,COVID-19パンデミックおよび今後の難題に対して,安全性,感染予防策,精神サポート,コミュニケーションおよびプログラミングの向上を図る必要がある.また,研究を更に進め,人々の口腔衛生を含めて地域単位での歯科クリニックへの影響を評価すべきである.

関係性:医療従事者,特に歯科医療従事者がCOVID-19に感染する危険性が最も高く,ウィールスの感染拡大を予防するのに重要な役割を担う.

キーワード:COVID-19,パンデミック,影響,歯科医療教育,歯科医療実務.

Key words:COVID-19, pandemic, impact, dental education, dental practice.

1. 緒言

2019年12月初頭に,中国の武漢市で病因の不明な肺炎が突発的に生じた.その全症例が武漢華南海鮮卸売市場と関連性があるとされた.1

この疾患の病原体は,2019年新型コロナウィルス(2019-nCoV)と特定された.その後,2020年2月に,世界保健機構(World Health Organization: WHO)により,COVID-19と名付けられた.COVID-19の病原ウィルスであるベータコロナウィルス(SARS-CoV-2)により,人間の下気道に病変が生じ,肺炎症状が表れる.2

COVID-19は,重症急性呼吸器症候群(SARS-CoV)や中東呼吸症候群(Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus(MERS-CoV))といった他の流行性CoVと姉妹関係にあると考えられている.2020年1月30日,WHOは,この突発的な発生に対し,「国際的に懸念される公衆衛生上の緊急事態」を宣言した.2020年2月26日に,アメリカ合衆国で,初の,中国が感染源ではないコロナウィルス感染者が確認された.2020年2月28日に,WHOは,CoVが大流行する危険度を「非常に高い」に引き上げ,その後3月に,パンデミック宣言を表明した.3

COVID-19は,呼吸器疾患や肥満,糖尿病といった他の併存疾患のある高齢の男性がより罹患し易いと報告されている.潜伏期間は7日から24日と区々であり,臨床症状も無症状から軽度の症状(発熱や乾性咳,喉の痛み),死に至る重度の致死性の合併症や急性呼吸窮迫症候群まで多岐にわたる.4

COVID-19は,CoV感染と同様に人獣共通感染症として報告され,コウモリやセンザンコウ由来の感染症が人間に伝播するとされていた.SARS-CoV-2感染患者の鼻咽腔分泌物や唾液分泌物に多く存在し,主に環境中に飛散する呼気中や飛沫との接触により伝播する.5

ニューヨークタイムズ誌が報道した記事によると,COVID-19に感染するリスクの最も高い医療従事者のランキングをしたところ,歯科医療従事者がランキングの上位層に上がっていた.6,7

COVID-19の主な感染経路は,直接接触感染および飛沫感染である.その他にも,唾液やエアロゾル(空中)感染により感染し得る.歯科治療には,多量の飛沫やエアロゾルの産生が伴うため,歯科医療従事者および患者に感染する危険性が存在する.6,8-11

歯科医療従事者は,歯科医療独特の業務に携わるため,COVID-19に感染する危険性が特に高い.患者と対面して意思疎通をし,唾液や血液,その他の体液と接触する頻度が多い.先の尖った高速ロータリーや超音波計測機を使用することにより,歯科医療業務において,特に無症状患者や軽症患者から感染する危険性が更に高まるため,感染防止策を確実に,徹底的に実施する.6,9,11-14

歯科医療従事者は,ウィルスの伝播を防止する上で重要な役割を担う.パンデミック期間中,患者や歯科医療従事者自らに健康的であり,安全な環境を維持すべく,必要な予防措置や感染防止策を講じることが必要不可欠である.8,10

多くの国の歯科大学では,血液感染に比べ,飛沫や空気感染に関する感染防止の情報や教育,実習がカリキュラムに十分盛り込まれていない.12 アメリカ合衆国の世論調査によると,大半の教育機関では,感染防止の教育に充てた授業が独立して存在せず,教室の授業や臨床講義の実物説明の場で触れる程度である.15 医科大学の方針やプロトコルを定期的に再評価し,将来起こり得るパンデミックに備え,優先順位を見直して不測の事態への具体的な対応策を盛り込むべきである.16

北米での調査によると,個人開業や教育機関において,COVID-19のパンデミックにより歯科医療業務に多大な影響が生じた.多くの歯科医療従事者は,業務上,感染する危険性が高く,仕事量が膨大化したことから,仕事に関係するストレス増や不安増を訴えている.17 Hung等が行った調査によると,18 ユタ州の歯科大学では,COVID-19が歯科医療の教育に多大な影響を及ぼし,歯科大生のストレスが増している.

Shacham等19の報告によると,COVID-19勃発期間中に,イスラエルの歯科医療スタッフの精神的苦痛が強まっている.香港で行われた調査では,感染防止策の有効性に自信は持ちつつも,歯科大生を含め,医療系学生全体が高ストレスを訴えている.20 中国で実施された調査によると,COVID-19による心理的な影響や不安について,回答者のうち,半分が中程度,三分の一が強程度と回答した.21 Duruk等22によると,自身および家族に対して懸念を示しているトルコ人歯科医が90%を超えていた.

調査により,歯科医療業務の再開について,イタリア人歯科医のリスクの捉え方を評価した.歯科医は,正式に感染形式についての情報を伝達されていたにも関わらず,不安を持ち,COVID-19の勃発期間中に安全に仕事する自信に欠けていた.23

世界30ヶ国の一般歯科医を対象に調査評価を実施したところ,パンデミックおよびCOVID-19に感染する高い危険性に対し,その三分の二を超えた人数の間で不安および恐怖が高まっていた.その大半は,勧告された米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)のガイドラインによる,最近の歯科医療治療のプロトコルの修正やサービスの変更について知っていた.24

Nelson等が実施した調査25では,パンデミックに対するアメリカ合衆国における社会の懸念や個人の行動を評価した.その大半がCOVID-19に対応すべく生活習慣を変え,三分の二が強いもしくは極めて強い懸念を抱いていた.

社会距離を確保し,対面での会話を要する授業や教育,臨床活動を最小限にする必要性が発表された後,歯科医療教育に対し,COVID-19の影響が即座に及んだ.オンライン講義,ウェビナー,コンピューター使用試験等の代替教育への移行が開始した.歯科大生の間で,COVID危機の間に感染する恐怖心によるストレスや悪影響の発現が見られた.そのため,精神的サポートやカウンセリングの必要性が増した.6

COVID-19は,歯科医療教育や研究,臨床診療に悪影響を与え,将来の応募者の減少も含め,長期的な影響が及ぶ可能性が存在する.6 大々的な介入措置として人々の健康や安全を守り,ウィルスの拡大を抑制すべく,臨床活動や外科活動が大幅に制限され,COVID-19により,医療・歯科医療業界に,多大な経済的損失がもたらされた.26

3. 結果

3.1 人口統計

2020年9月の春学期後半に,UTHSA, SoD教授陣やスタッフ,学生全体が,COVID-19の歯科医療教育および業務に関する影響についての調査に自発的に参加するように呼びかけられた.回答者は,教育施設の環境における経験および不安に対する大学側の対応について質問された.学期の後半期に,通常の業務の一貫として,あるいは学業における修得単位を充たすために歯科医療の業務を再開した,その一部の回答者は,コロナとの接触を減らすべく課された新たな規則の下で歯科医療業務を再開するにあたっての難題について質問された.

参加を呼びかけられた1230人の回答者のうち,UTHSA, SoD関係者合計356人の回答者(回答率29%)が調査の第一部(一般的な質問)に回答した.このグループのうち,204人(57%)が調査の第二編(臨床に関する質問)に回答した.回答者の構成は,図1の表1の通りである.回答者の回答率を構成別にみると,教授陣51%,事務員・スタッフ27%,学位修得前の学生30%(歯学部生22%,歯科衛生士学科の学生38%)であり,学位取得後の学生もしくは上級教育受講者が24%であった.回答率による結果の比較検討はされていない.

調査第一部の回答者は,一般的にUTHSA, SoD成員の全体像を表したものであり,ヒスパニック系の比率が高い一方,数多くの外国人留学生が集まる町に所在していた.第一部の回答者は,女性が三分の二を占めていた.主に臨床に関する質問から成る第二部の回答者は,男性の数が僅か上回り,年齢が高めのヒスパニック系もしくは白人であり,教授陣または三年生もしくは四年生の歯学大生が多くを占めていた.

3.2 パンデミック期間中の一般的な難題

一連の質問で,回答者は,自らが思うことや意見を5段階評価するように指示された.回答は,二つに分けられた.回答は,肯定的な回答(ややそう思う,ある程度~かなりそう思う)および否定的な回答(多分そう思わない,そう思わない)であり,カイ二乗統計検定により,各回答者グループの共通性もしくは他と異なるグループ一つ以上を探した.この部分の調査結果は,表2に表示されている通り,大学における活動内容別に分類された.

91%の回答者が,パンデミック期間中のUTHSAのサポートに資する対応力に,満足しているという結果が出た.半数を超えた人数の教授陣(54%)および事務員・スタッフ(67%)から成るグループがCOVID-19期間中のリモートワークやリモート学習に対して,ある程度簡単からとても簡単であると回答した一方,半数を超えた学生(66%)には,簡単ではないことが判明した.回答者は,COVID-19が自らの健康全般,安全性や状態(86%)およびUTHSA(94%)への影響に懸念を示した.回答者全体のうち,調査時に自身もしくは世帯員のCOVID-19検査結果が陽性であったと答えた回答者は僅か5人であった.

調査の他の質問の一式で,UTHSA, SoD回答者に,具体的に,以下の二つのものに関係する対応措置に重要度の順位付けをするように求めた.COVID-19に関する主な最新情報源(図2)およびリモートワークやリモート学習に関する難題(図3)である.回答評価に二つの方法が用いられた.1)重要度の平均: 最も重要な対応措置を1とし,二番目に重要なものを2とし,その他の項目も重要度に応じて番号付けし,全回答者が番号で表した重要度の平均値を計算した.2)好感度の格付け: 質問数により,対応措置について,上位二位あるいは三位まで格付けした回答者の平均を報告した(図2,3,4).

SoDコミュニティー調査の回答者は,他の情報源に比べ,UTHSA COVID-19ウェブサイトおよびバーチャルミーティングの2つを,最も重要な主要情報源と格付けする割合が多く(56%),これらを最下位に格付けする成員数が最も少なかった.インターネットのサーチエンジンやテレビチャンネル・ニュースの重要度格付けは,ほぼ同程度であった.出版までに要する時間の長い季刊誌や出版物は,半分を超えた人数の回答者により,ほぼ最下位に格付けされ,これは当然ともいえる.興味深いことに,ソーシャルメディアの好感度格付けが最下位にあった.

難題については,リモートワーク・学習するにあたり,ツールや情報のアクセスが最上位を占める頻度が最も多かった.インターネットの接続,実際に身を置いて仕事する空間,教職員スタッフや同僚とのコミュニケーションの維持が,重要度のほぼ最上位を占めた.難題に関する項目のうち,COVID-19に関する不安や家族の成員の世話が,コミュニティー全体にわたり,最も小さな難題として格付けされた(それぞれ45%,60%).注意散漫により規則正しい日程を乱されることが難題の一つであったことも注目に値する.これは,回答者全体の三分の一が,難題項目の中で最も重大なものとみなし,学生の半数を超えた人数および若年層が,注意散漫を重大度のほぼ最上位に格付けした.

3.3 歯科医療業務の再開に関する難題

臨床に関する調査の回答者204人は,8つの質問・記述に対し,自ら思うことや意見を5段階評価で回答するように求められた.回答内容は表3に表示されSoDの成員別に再分類され,二つの分類に分けられた.他グループとの回答が異なるグループが一つ以上存在するか否かの確認をするにあたり,カイ二乗検定により算出された値がp<0.05であった場合,統計的優位性が得られた.

3.3.1 重要度に関する結果

- 回答者全体の80%を超えた人数が,歯科医療業務を再開する心の準備が心持ちあるいはそれ以上に整っていた.教授陣および学位取得後の学生,男性,年齢が高めで最も経験が豊富な回答者が最も心の準備が整っていた.

- 87%を超えた回答者が,歯科医療に,考慮すべき難題や長期的な影響が伴うと思った(ある程度またはかなり).難題や影響が伴うと確信する女性の数が男性の数をやや上回り,歯科医療の経験が少ない回答者は,5年以上の経験を持つ回答者に比べ,長期的な影響に対する実感が薄かった.

- 90%ほどの回答者は,安全措置やエアロゾルを産生する歯科治療実施時に,UTHSAから出た安全対策やPPEにより守られる自信がややある,あるいはそれ以上にあると回答した.教授陣が最も自信を持っていた一方,学位取得前の学生の自信度がより低い傾向にあった.男性および年齢が高めのグループの自信度が高かった.

- 約60%が,COVID-19により,患者の歯科治療が変わったと答え,80%が,COVID-19により効率に支障が出ると感じた.年齢が高めのグループが最もこれを実感していた.治療を変える必要性を実感していた回答者は,女性が多い一方,男性は効率性に対しての懸念をより強く持っていた.歯科衛生科の学生は,治療を変える必要性を最も強く実感していた一方,教授陣の間ではその実感が最も薄く,効率性については,事務員・スタッフの意識が最も低かった.

- 約60%が,選んだ歯科のキャリアを多分または確実に見直さない,約65%が,多分または確実に他人に歯科学の勉強を勧めると回答した.選択したキャリアに対して最も両面感情も持っていたグループは,事務員・スタッフおよび女性,若年層の回答者であった.

回答者は,ロックダウン解除後に歯科医療を再開するにあたり,直面する9つの難題の重要度を順序付けするように求められた(図4).SoDコミュニティーの間では,他の難題に比べ,圧倒的にPPEの入手および歯科治療の通院患者を探すことを重要度上位3に上げる回答者が多かった(>50%).COVID-19勃発に関する懸念が,難題のほぼ最上位に格付けされていたにも関わらず,恐怖や不安は最下位に格付けされた.

3.3.2 重要度に関する結果:

- 他のグループに比べ,学位取得後の学生のPPE入手に対する懸念が最も強く,学位取得前の学生の懸念が最も少なかった.

- 学位取得前の学生が最も懸念としたところは,十分な患者数の確保であり,患者の歯科医療サービスを受ける財源に対する懸念度もより高かった.これらの懸念は,卒業単位を充たすための十分な臨床経験の確保に関する不安を反映したものである可能性がある.

- 教授陣の間では,患者のCOVID-19感染検査に関する懸念がより高い一方では,恐怖や不安に関する懸念度は最下位にあった.

- 教授陣,最年長でもっとも経験が豊富なグループ除き,全グループの間では,大学やクリニックの財務上の損失に対する懸念度がほぼ最下位にあった.

4. 考察

COVID-19のパンデミックは,公衆衛生上,深刻な難題を作り出すことにより,世界中を脅かし,医療従事者,特に歯科医療提供者に多大な影響を及ぼした.最新のデータによると,クローバル規模で感染拡大を防止する努力がなされていたにも関わらず,世界中で,COVID-19の感染者数が増加し続け,何百万人もの患者が罹患し,何百何千人もの死者が報告された.

歯科医療において,COVID-19に感染する危険性が高いため,必要に応じて患者との直接接触を減らすべく,パンデミックの初期に,従来の教育実習を中断することにより,代替教授法およびシミュレーションによる臨床技術の演習を改善する機会が生まれた.

Iyer等16によると,歯科大学の経営側が直面する最も大きな難題は,最重要事項である,学生やスタッフ,患者の健康確保であると同時に,変遷する環境や国家政策の流れを把握し続け,確実に学生の教育を継続させることである.経営側は,研修医および学生が受ける研修の中断を最小限にし,このような危機の最中に,将来のパンデミックに向けてコミュニティーに良い結果をもたらす助けとなる準備をすべく,カリキュラムのおける学内実習および専門連携教育の強化を力説した.

歯科医療従事者は,歯科医療の特殊な職柄から,更に患者と対面して会話することから,COVID-19に感染する危険性が高い.6,7,9,11-14 しかしながら,臨床医から患者へ,またその逆も同様に,感染が起きた報告は存在しない.感染拡大防予防措置やCOVID-19感染を防止する健康かつ安全な環境を維持することにより,これまでに高い効果が得られた.8,10

この調査では,回答者は,自らの健康一般,安全,状態,更にUTHSAにもたらされるCOVID-19の影響に懸念を持っていた.大半は,歯科医療に難題や長期的な影響が伴うという意見で一致した.過去の調査でも6,16-18歯科医療のスタッフや学生の間で高まり得るストレスや不安,恐怖を含めて,COVID-19が歯科医療の教育や業務に多大な悪影響を及ぼし,歯科医療に長期的な影響が予想されるという意見で一致している.女性であることや学生の身分,具体的な身体的症状が,心理的な影響やストレス,不安や鬱の悪化との関連性を有していた.21 COVID-19のパンデミックによる心理的な影響に対する調査は,多くの国(イギリスやアメリカ合衆国,イスラエル,香港,中国,トルコ,イタリア,サウジアラビア,パキスタン,その他の国)で行われ,全ての国において,高度のストレスや恐怖,不安が報告された.6,16-25

Spagnuolo等26が調査したところ,COVID-19が臨床活動に大幅な制限を課し,ウィルスの拡大防止をすべく対策実施を要したことから,歯科医療業界にの財政に多大な影響を及ぼしたという点で,我々の調査結果と一致している.

SoDコミュニティーの報告によると,パンデミック期間中の主要な最新情報源は,UTHSA COVID-19のウェブサイトおよびSoDリーダーシップとの週二回のバーチャルミーティングであり,インターネットのサーチエンジンやテレビチャンネル,ニュースがそれに続いた.それに対比して,トルコ人歯科医の調査報告によるとCOVID-19に関する歯科医の情報入手源は,公的機関のウェブサイトやソーシャルメディアのアカウントであり,回答者の約四分の一のみがCOVID-19に関する情報会議に参加した.22

我々の回答者の大半は,歯科医療業務を再開する心の準備が出来,アエロゾルを産生する歯科治療実施時に,UTHSAから出た安全対策やPPEにより守られる自信を持っていた.約60%が,COVID-19により歯科治療に変更が生じたと感じ,80%が,効率に悪影響が及ぶと感じた.それに対して,De Stefani等23の報告によると,イタリア人歯科医は,COVID-19感染を非常に危険と捉え,安全に歯科医療業務を再開する自信を持たず,感染拡大防止措置やPPEに対し疑いを持ち,自らの健康や業務における経済的・財政的な損失を危惧していた.適切なPPEの使用や入手,その他にもパンデミック期間における最新のプロトコルに対する意識についての不安も,幾つかの調査で報告されている.6,22-24

この調査では,リモートワーク・学習の困難な点や難題,歯科医療再開にあたっての難題を含め,その他の重要な問題点も評価した.過去に評価されていない多く内容がこの文献で取り上げられ,歯科医療の教育や実務に影響を及ぼしたCOVID-19に関する新たな難題が浮き彫りにされた.

4.1 限度

ここで留意すべき重要なことは,COVID-19パンデミックの初期に歯学科でこの調査が行われ,パンデミックの進行状況により,意見が変わり得る点である.

将来の調査では,人々の歯学医療および口腔衛生に対する長期的な影響を含め,コミュニティーの歯科医に対するCOVID-19パンデミックの影響を評価すべきである.

5. 結論

この調査で,回答者がパンデミック中のサポートに資するUTHSAの対応に満足していたことが判明した.回答者は,UTHSAでの,自らの健康全般,安全,状況に対するCOVID-19の影響に懸念を持っていた.過半数が,歯科医療業務を再開する心の準備が出来,講じられた安全対策の有効性やPPEの入手可能性に自信を持ち,歯科医療に難題や長期的な影響が伴うという意見で一致した.

パンデミック中の主要な最新情報源が,UTHSAのCOVID-19ウェブサイトや頻繁に行われるバーチャルミーティングであることが判明した.リモートワーク・学習時のツールや情報のアクセスも難題の上位として報告された.歯科医療業務の再開時は,PPEの入手や患者の流動が難題の最上位に格付けされた.COVID-19の勃発が全ての難題の中でほぼ最上位に格付けされたものの,恐怖や不安は,ほぼ最下位に格付けされた.

5.1 歯科医療教育および実務との関係性:

医療従事者,特に歯科医療従事者は,COVID-19に感染する危険性が最も高く,ウィルスの感染防止に大きな役割を果たす.

謝辞

著者は,この調査を遂行するにあたり,UT Health San Antonio歯学部長事務室のスタッフ一同には,ひとならぬご尽力を頂き,心より感謝申し上げます.Kristen Zapata女氏には,ご親切に調査票を配布頂き,特別に感謝申し上げます.データ分析にひとかたならぬ助力を頂き,Michael Mader氏およびEmmanuel Cortez氏,Jeremy Mercierに感謝申し上げます.

利害関係の衝突:著者は,利害関係の衝突が存在しないことを宣言する.

参考文献

- Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang Y‐W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92: 401–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25678.

- Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International Journal of Surgery 76 (2020) 71–76.

- Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- N. Chen, M. Zhou, X. Dong, et al., Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study, Lancet (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

- Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM. Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19): Implications for Clinical Dental Care. J Endod. 2020;46(5):584-595. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008.

- Barabari P, Moharamzadeh K. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Dentistry-A Comprehensive Review of Literature. Dent J (Basel). 2020;8(2):53. Published 2020 May 21. doi:10.3390/dj8020053.

- The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk—The New York Times. [(accessed on 2 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker-risk.html.

- Ge, Z., Yang, L., Xia, J., Fu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science B, 21(5), 361–368. https://doi. org/10.1631/jzus.B2010010.

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9.

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9. Published 2020 Mar 3. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9.

- Ionescu AC, Cagetti MG, Ferracane JL, Garcia-Godoy F, Brambilla E. Topographic aspects of airborne contamination caused by the use of dental handpieces in the operative environment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(9):660-667. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.002.

- Ghai S. Are dental schools adequately preparing dental students to face outbreaks of infectious diseases such as COVID-19? J Dent Educ. 2020; 1-3. In Press.

- Pan Y, Liu H, Chu C, Li X, Liu S, Lu S. Transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2 and protective measures in dental clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Dent. 2020;33(3):129-134.

- Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):481-487. doi:10.1177/0022034520914246.

- Porteous NB, Bizra E, Cothron A, Yeh C-K. A survey of infection control teaching in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(2):187-194.

- Iyer P, Aziz K, Ojcius DM. Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:718–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12163.

- Wu KY, Wu DT, Nguyen TT, Tran SD. COVID-19’s impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral Dis. 2020;00:1–4. https:// doi.org/10.1111/odi.13444.

- Hung M, Licari FW, Hon ES, et al. In an era of uncertainty: Impact of COVID-19 on dental education. J Dent Educ. 2020;1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12404.

- Shacham M, Hamama-Raz Y, Kolerman R, Mijiritsky O, Ben-Ezra M, Mijiritsky E. COVID-19 Factors and Psychological Factors Associated with Elevated Psychological Distress among Dentists and Dental Hygienists in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2900. Published 2020 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082900.

- Wong JG, Cheung EP, Cheung V, Cheung C, Chan MT, Chua SE, McAlonan GM, Tsang KW, Ip MS. 2004. Psychological responses to the SARS outbreak in healthcare students in Hong Kong. Med Teach. 2004;26(7):657–659. doi:10.1080/01421590400006572.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. Published 2020 Mar 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729.

- Duruk G, Gümüşboğa ZŞ, Çolak C. Investigation of Turkish dentists' clinical attitudes and behaviors towards the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e054. doi:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0054.

- De Stefani A, Bruno G, Mutinelli S, Gracco A. COVID-19 Outbreak Perception in Italian Dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3867. Published 2020 May 29. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113867.

- Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, et al. Fear and Practice Modifications among Dentists to Combat Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. Published 2020 Apr 19. doi:10.3390/ijerph 17082821.

- Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, et al. US Public Concerns About the COVID-19 Pandemic from Results of a Survey Given via Social Media [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 7]. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1020-1022. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020. 1369.

- Spagnuolo G, De Vito D, Rengo S, Tatullo M. COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview on Dentistry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2094. Published 2020 Mar 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph 17062094.

JICD,Vol.2,No.1,e002,2021

ENG / CHN / JPN / ESP

Mitigando El Impacto de COVID-19 en la Educación Dental y la Reanudación de la Atención al Paciente: Experiencia en UT Health San Antonio

Corresponding Author:

Enas A. Bsoul, DDS, MSc, MS

Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229

Email: [email protected]

Author:

Peter M. Loomer, BSc, DDS, PhD, MRCD(C), FACD

Professor and Dean, School of Dentistry, UT Health San Antonio

Email: [email protected]

Traducción al Español: Dr. Pablo Serech

Resumen

Propósito / Objetivos: El propósito de este estudio fue evaluar el impacto de la pandemia COVID-19 en la facultad, el personal y los estudiantes de UT Health San Antonio (UTHSA), Facultad de Odontología (SoD), y su disposición para reanudar la práctica dental con medidas de seguridad establecidas.

Métodos: Se distribuyó un estudio de encuesta observacional aprobado por la Junta de Revisión Institucional de UTHSA a los miembros de UTHSA, SoD utilizando el software Qualtrics. La encuesta se completó de forma anónima. Los datos se analizaron mediante el software de cálculo estadístico R, la prueba de Chi-Cuadrado y la prueba de Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney.

Resultados: En general, la mayoría de los encuestados estaban satisfechos con los recursos que UTHSA proporciona para ayudarlos durante la pandemia (91%), confiaban en las precauciones de seguridad y el equipo de protección personal en la escuela (90%), se sentían preparados para reanudar la práctica dental (81%), y estuveron de acuerdo en que existen desafíos (87%) e impactos a largo plazo (94%) en la odontología. La mayoría estaba preocupada por los impactos del COVID-19 en UTHSA (94%) y en su salud general, seguridad, bienestar físico y psicológico (86%).

Conclusiones: Existe un impacto sanitario, psicológico y económico significativo del COVID-19 en los profesionales dentales; de ahí la necesidad de mejorar la seguridad, las precauciones para el control de infecciones, el apoyo psicológico, las comunicaciones y la programación en torno a la pandemia de COVID-19 y los desafíos futuros. La investigación adicional debe evaluar el impacto de la pandemia en las clínicas dentales comunitarias, incluidos los efectos a largo plazo sobre la salud bucal de la población.

Implicaciones: Las profesiones de la salud, en particular la odontología, tienen el mayor riesgo de contraer la infección por COVID-19 y desempeñan un papel importante en la prevención de la transmisión del virus.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, pandemia, el impacto, la educación dental, práctica dental.

1. Introducción

A principios de diciembre de 2019, surgió un brote de neumonía de etiología desconocida en la ciudad de Wuhan, China. Todos los casos estaban vinculados al mercado mayorista de mariscos Huanan de Wuhan.1

El agente causante de la enfermedad se identificó como un nuevo coronavirus de 2019 (2019-nCoV). La enfermedad fue posteriormente denominada COVID-19 por la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) en febrero de 2020. El betacoronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) que causa el COVID-19 afecta el tracto respiratorio inferior y se manifiesta como neumonía en humanos.2

COVID-19 se considera un pariente de otras epidemias de CoV como el coronavirus del síndrome respiratorio agudo severo (SARS- CoV) y el coronavirus del síndrome respiratorio de Oriente Medio (MERS- CoV). El 30 de enero de 2020, la OMS declaró el brote como una emergencia de salud pública de importancia internacional. El 26 de febrero de 2020 se registró en Estados Unidos el primer caso de coronavirus, que no se contrajo por primera vez en China. La OMS elevó la amenaza epidémica de CoV a un nivel "muy alto" el 28 de febrero de 2020 y la declaró pandemia a finales de marzo.3

Se ha informado que COVID-19 afecta con mayor probabilidad a los hombres mayores con otras comorbilidades, como enfermedades respiratorias, obesidad y diabetes. El período de incubación puede variar entre 7 y 24 días, con síntomas clínicos que van de ninguno a leve (fiebre, tos seca y dolor de garganta) a muy graves con complicaciones fatales y síndrome de dificultad respiratoria aguda.4

COVID-19, similar a otras infecciones por CoV, se informó como zoonótico, se cree que se originó en murciélagos y pangolines y luego se transmitió a los humanos. El SARS-CoV-2 estaba profusamente presente en las secreciones nasofaríngeas y salivales de los pacientes afectados, su diseminación fue principalmente por gotitas respiratorias / contacto por naturaleza.5

Un artículo publicado por la revista The New York Times clasificó a las profesiones de la salud con mayor riesgo de infección por COVID-19, entre las cuales los profesionales dentales ocuparon el primer nivel del ranking.6,7

Las principales rutas de transmisión de COVID-19 son el contacto directo y la transmisión por gotitas. Otra ruta posible es la transmisión de saliva y aerosoles (en el aire). La naturaleza de los procedimientos dentales plantea riesgos potenciales de transmisión de infecciones al personal de atención dental y a los pacientes, ya que generan cantidades significativas de gotitas y aerosoles.6,8-11

Los profesionales dentales, están especialmente en alto riesgo de infección por COVID-19 debido a la peculiaridad de la práctica dental; comunicación cara a cara con los pacientes y exposición frecuente a saliva, sangre y otros fluidos corporales. El uso de instrumentos rotativos y ultrasónicos afilados y de alta velocidad aumenta el riesgo de infección en las consultas dentales, particularmente en pacientes asintomáticos o con síntomas leves, lo que exige protocolos de control de infecciones estrictos y efectivos.6,9,11-14

Los profesionales de la odontología juegan un papel importante en la prevención de la transmisión del virus. Es esencial que implementen las precauciones necesarias y las medidas de control de infecciones para mantener un ambiente saludable y seguro para los pacientes y para ellos mismos durante la pandemia.8,10

En muchos países, en comparación con las infecciones transmitidas por la sangre, la información sobre el control de infecciones, la educación y la práctica con respecto a las infecciones por gotitas y transmitidas por el aire en el plan de estudios de la mayoría de las escuelas de odontología son limitadas.12 En una encuesta de EE. UU., Se descubrió que la mayoría de las escuelas no tenían un curso independiente para enseñar control de infecciones y solo usaban conferencias en el aula y demostraciones clínicas.15 Las políticas y protocolos de las escuelas de odontología deben reevaluarse periódicamente y volver a priorizar para incluir un plan de contingencia detallado en caso de pandemias futuras.16

Un estudio en América del Norte encontró que la práctica de la odontología se vio significativamente afectada por la pandemia de COVID-19 en la práctica privada y en los entornos académicos. Muchos profesionales dentales han informado de un aumento del estrés y la ansiedad relacionados con el trabajo debido al alto riesgo laboral de infección y al aumento significativo de las tareas.17 Un estudio de encuesta de Hung et al,18 llevado a cabo en una escuela de odontología en Utah, encontró un impacto significativo de COVID-19 en la educación odontológica, con mayores niveles de estrés entre los estudiantes de odontología.

Shacham et al19 informó elevado nivel de estrés psicológico experimentado por personal dental israelí durante el brote COVID-19. En un estudio de encuesta en Hong Kong, todos los estudiantes de salud, incluidos los estudiantes de odontología, informaron niveles altos de estrés a pesar de tener confianza en los procedimientos de control de infecciones.20 Un estudio realizado en China reveló que el impacto psicológico y la ansiedad del COVID-19 fueron calificados como moderados a severos por aproximadamente la mitad y un tercio de los encuestados, respectivamente.21 Duruk et al22 encontraron que más del 90% de los dentistas turcos estaban preocupados por ellos mismos y sus familias.

Un estudio de encuesta evaluó la percepción de los dentistas italianos sobre los riesgos asociados con la reanudación de la práctica dental. Aunque los dentistas estaban debidamente informados sobre los modos de transmisión, estaban preocupados y no confiaban en poder trabajar de manera segura durante el brote de COVID-19.23

Los odontólogos generales de 30 países diferentes en todo el mundo fueron evaluados en un estudio de encuesta que encontró que más de dos tercios tenían ansiedad y miedo elevados debido a la pandemia y estaban en alto riesgo de contraer COVID-19. La mayoría conocía los cambios recientes en el protocolo de tratamiento dental y los servicios modificados de acuerdo con las pautas recomendadas por los CDC (Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades).24

Un estudio de encuesta de Nelson et al25 evaluó las preocupaciones del público estadounidense y las acciones individuales en respuesta a la pandemia. La mayoría de los encuestados informaron haber realizado cambios en su estilo de vida en respuesta al COVID-19 y dos tercios estaban muy o extremadamente preocupados.

El impacto del COVID-19 en la educación odontológica fue inmediato después de anunciar la necesidad de un distanciamiento social y minimizar las actividades docentes, educativas y clínicas que requieren la comunicación cara a cara. Se instituyó el cambio a métodos de enseñanza alternativos, como conferencias en línea, seminarios web y exámenes por computadora. Se ha demostrado que los estudiantes de odontología están estresados y afectados negativamente por el miedo a infectarse durante la crisis de COVID ; por lo tanto, se ha necesitado una mayor necesidad de servicios de asesoramiento y apoyo psicológico.6

COVID-19 ha tenido un impacto negativo en la educación, la investigación y la práctica clínica odontológicas con posibles efectos a largo plazo, como una reducción en el número de futuros solicitantes.6 COVID-19 también ha tenido un gran impacto en la economía del sector médico / dental al limitar significativamente las actividades clínicas y quirúrgicas, una intervención drástica para proteger la salud y la seguridad de las personas y contener la propagación del virus.26

3. Resultados

3.1 Demografía

Se pidió a todo el grupo de profesores, personal y estudiantes de UTHSA, SoD que participaran voluntariamente en una encuesta sobre el impacto de COVID-19 en la educación y la práctica dental en la segunda mitad del semestre de primavera de 2020. Se les preguntó a los encuestados sobre su experiencia de estar en un entorno escolar y la respuesta de la universidad a sus inquietudes. A un subconjunto de los encuestados, aquellos que regresaron a la escuela en la última parte del semestre para reanudar la práctica dental como parte de sus deberes laborales habituales o requisitos académicos, se les preguntó sobre los desafíos relacionados con la reanudación de la práctica dental bajo nuevas reglas diseñadas para reducir la exposición. al coronavirus.

De los 1230 encuestados invitados, un total de 356 encuestados (tasa de respuesta del 29%) asociados con UTHSA, SoD completaron la primera parte de la encuesta (preguntas generales). De ese grupo, 204 (57%) completaron la segunda parte (preguntas relacionadas con la clínica) de la encuesta. Los datos demográficos informados por los encuestados se muestran en la Tabla 1 y la Figura 1. Las tasas de respuesta entre varios tipos de encuestados totales fueron: 51% del profesorado, 27% de la administración / personal, 30% de los estudiantes predoctorales (22% de los estudiantes de odontología y 38% de los estudiantes de higiene dental) y 24% de los estudiantes de posdoctorado / educación avanzada. Los resultados no fueron ponderados por la tasa de respuesta.

Los encuestados de la primera parte de la encuesta fueron en general representativos de la población total de esta UTHSA, SoD, que se encuentra en una ciudad con una alta proporción de residentes hispanos pero que también atrae a una gran cantidad de estudiantes internacionales. Dos tercios de los encuestados en la primera parte eran mujeres. Los encuestados de la segunda parte de la encuesta centrada en la clínica tenían un poco más de probabilidad de ser hombres, mayores e hispanos o blancos, también tenían más probabilidades de ser profesores y estudiantes de odontología de tercer o cuarto año.

3.2 Retos Generales Durante la pandemia